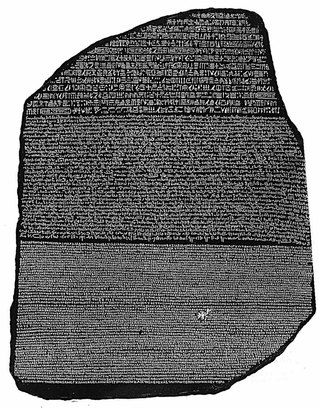

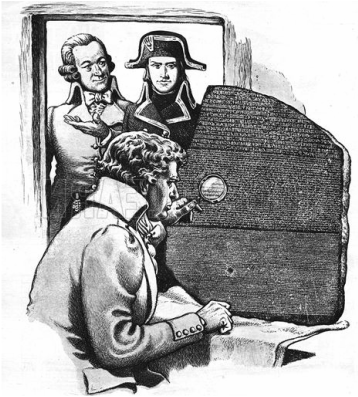

When the last Egyptian Pharaoh, Queen Cleopatra, died in the year 30 BCE control of Egypt was ceded to the Roman Empire who ruled over it for the next four centuries. Not long after Cleopatra's death, the early part of the Common Era (CE) was marked by a slow but steady growth in Christianity throughout the Roman Empire. Egyptian history and the birth of Christianity collided when, in 391 CE, the Byzantine Emperor Theodosius I closed all pagan temples throughout the empire. That included temples to the Egyptian gods. Theodosius's action ended a 4000 year old tradition and the message of the ancient Egyptian language was lost for the next 1500 years. It was not until the discovery of the Rosetta stone (pictured at right) and the work of Jean-Francois Champollion, a French Egyptologist, that a light was shone on the mysteries of the ancient Egyptians. Today, by virtue of the vast quantity of their literature, we know more about Egyptian society than most other ancient cultures.

What are hieroglyphics?

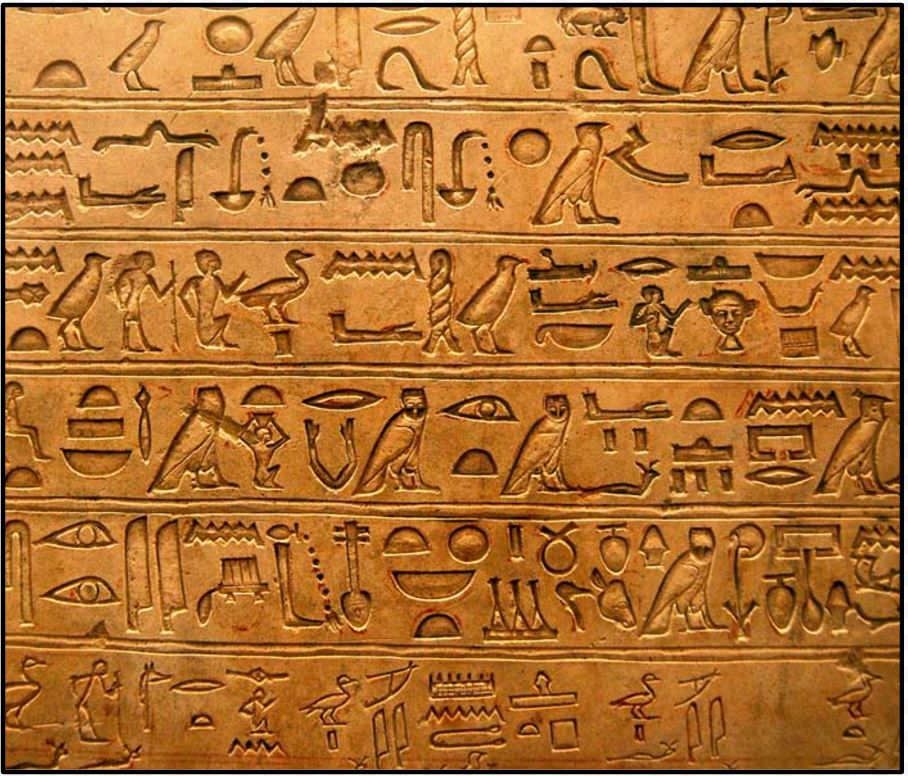

Egyptian Writing: We know a great deal about the ancient Egyptians because they loved to write, especially on walls! They wrote about their gods, their rulers, and their daily life. They wrote stories and poems and wonderful myths. To do so they used a sort of picture writing called hieroglyphics, which comes from the Greek and means “sacred inscriptions.” Archaeological evidence suggests that the ancient Egyptians started to write with hieroglyphs shortly before King Narmer united Upper and Lower Egypt in 3100 BCE. It's probably no coincidence that a common writing system appeared around this time. A common system of record keeping and a common written language were, no doubt, helpful when Narmer began to command and control a region as alrge as ancient Egypt.

Like other early writing systems, Egyptian hieroglyphics used pictographs to record ideas. In fact, it is suggested that Egyptian writing can be traced to early Sumerian cuneiform. Unlike cuneiform, however, Egyptian hieroglyphics remained greatly unchanged for over 3000 years.

What was a scribe’s job?

Neither reading nor writing hieroglyphs was easy. An Egyptian scribe would need to know over 1000 symbols. More, Egyptian hieroglyphics didn't have rules like we do today. For instance:

What was a scribe’s job?

Neither reading nor writing hieroglyphs was easy. An Egyptian scribe would need to know over 1000 symbols. More, Egyptian hieroglyphics didn't have rules like we do today. For instance:

- Hieroglyphics could be written in almost any direction; left to right, right to left, or top to bottom. The reader would figure out which way to read it by the direction of the symbols. A head or hand pointing right or an animal facing right would indicate that readers should read the script from right to left.

- There was no punctuation. (Hmmmm, just like a lot of 6th grade writing I see... Perhaps you are an ancient Egyptian who has returned to teach me more about your great civilization.)

- One of the goals of writing hieroglyphics was that the writing should look like art. Indeed, hieroglyphs can be beautiful to look at.

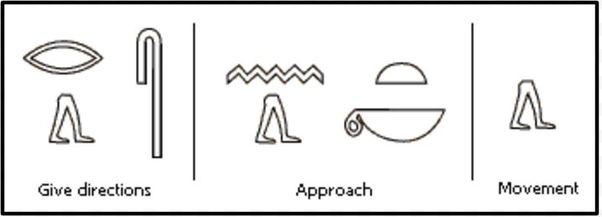

- A single picture symbol could stand for a whole word, called an ideogram, or a sound, called a phonogram. For example, a picture of an lion could mean the word "lion" or the letter "L".

- To make things even more difficult, Ideograms could represent either the specific object written or something closely related to it. For example, the hieroglyphic symbol of a pair of legs might represent the noun movement. When combined with other glyphs, the symbol could represent the verb to approach, or the concept to give directions.

Although very pretty, another problem with using hieroglyphs is that they took time to draw. Due to that, the ancient Egyptians needed another system to scribble things down quickly. Later, their scribbles could be translated into hieroglyphics. That system, a sort of short hand, was called hieratic writing. Not everyone knew how to read hieratic. You had to be educated to read it. The people who could read it, and used hieratic to write things down, were called scribes. A scribe’s job was to write things down.

It took years of education and practice to become a scribe. Typically, training to become a scribe would start at the age of six or seven. All of the work was worth it, however. Being a scribe was a good job in Ancient Egypt. Scribes didn't have to pay taxes or enter the army. They were very highly thought of and only the children of the wealthy got the opportunity to train as scribes.

By 700 BCE, the ancient Egyptians had developed yet another style of writing called Demotic. Demotic was fast. Like hieratic writing, demotic writing was used for administrative documents, accounts, legal texts, and letters, as well as mathematical, medical, literary, and religious texts. Most often, scribes used a brush and ink to write on a type of paper called papyrus. Papyrus paper was made from a tall reed like plant called Papyrus. The Egyptians cut thin strips of the inner stem of the plant to make the paper. They arranged the strips in two layers, one horizontal and the other vertical. They would then cover their work with a linen cloth and hammer it with a mallet or with stones. The papyrus strips would bind together over time making a single flat sheet to write on.

The use of hieroglyphics declined during Roman rule and ceased altogether after Emperor Theodosius I closed all non-Christian temples in 391 CE. As time went on, fewer and fewer people could read the old script. One day, there was no one left who could read this ancient language at all. Everyone had forgotten. That was a problem. When modern archaeologists first found walls and scrolls full of writing, they were excited. But no one could read a word. No one had any idea what the hieroglyphic symbols meant.

What is the name of the stone that helped archaeologists crack the hieroglyphics code?

By 700 BCE, the ancient Egyptians had developed yet another style of writing called Demotic. Demotic was fast. Like hieratic writing, demotic writing was used for administrative documents, accounts, legal texts, and letters, as well as mathematical, medical, literary, and religious texts. Most often, scribes used a brush and ink to write on a type of paper called papyrus. Papyrus paper was made from a tall reed like plant called Papyrus. The Egyptians cut thin strips of the inner stem of the plant to make the paper. They arranged the strips in two layers, one horizontal and the other vertical. They would then cover their work with a linen cloth and hammer it with a mallet or with stones. The papyrus strips would bind together over time making a single flat sheet to write on.

The use of hieroglyphics declined during Roman rule and ceased altogether after Emperor Theodosius I closed all non-Christian temples in 391 CE. As time went on, fewer and fewer people could read the old script. One day, there was no one left who could read this ancient language at all. Everyone had forgotten. That was a problem. When modern archaeologists first found walls and scrolls full of writing, they were excited. But no one could read a word. No one had any idea what the hieroglyphic symbols meant.

What is the name of the stone that helped archaeologists crack the hieroglyphics code?

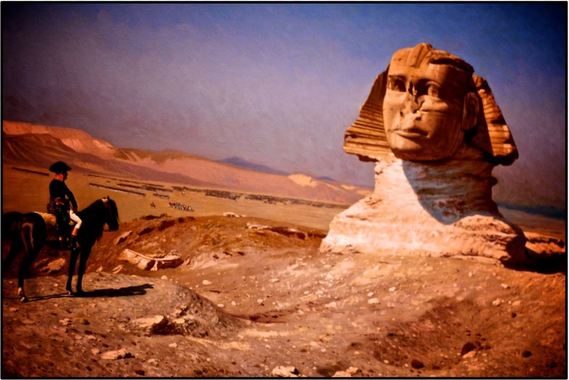

Following in the footsteps of the Greeks and Romans, Napoleon led an expedition to Egypt hoping to add it to his empire.

Following in the footsteps of the Greeks and Romans, Napoleon led an expedition to Egypt hoping to add it to his empire.

Breaking the Code: During the French occupation of Egypt from 1798 to 1801, a group of French soldiers and engineers working near the town of Rosetta (known in Egypt as Rashid) uncovered a large stone. The stone they found had ancient inscriptions containing the same text written three different ways. At the bottom, the writing was in Greek. Archaeologists could read Greek. The piece written in Greek told a story. The middle section was written in Demotic. Archaeologists could read that, too. The piece written in Demotic told the same story! Archaeologists were pretty excited. If the bottom piece written in Greek told one story, and the middle section written in Demotic told the same story, well then, it was very possible that the top section, written in hieroglyphics, told the same story, too! It was an exciting discovery, but archaeologists needed more.

Artifacts seized by Napoleon and his troops, including obelisks and the Rosetta Stone made their way back to France where the Egyptologist, Jean-Francois Champollion, worked things out. He discovered that some hieroglyphs stood for a single sound - a part of a word. Other hieroglyphs stood for an idea - a whole bunch of words. Champollion was the first modern person who was able to read hieroglyphs. During his work, Champollion also noted that certain groups of hieroglyphs on the Rosetta Stone were surrounded by a carved oblong loop. The loop, called a cartouche, separated the names of kings and queens from large bodies of text.

By now, Champollion knew enough hieroglyphs to confirm that the cartouches on the Rosetta Stone contained the name of one of the Greek rulers of Egypt, Ptolemy V. As Champollion examined more cartouches, he observed that some of the glyphs matched between Ptolemy’s cartouche and other cartouches. Champollion determined that certain glyphs in the cartouches phonetically spelled out the names of certain Greek rulers of Egypt. Using this knowledge and an ingenious reading of ideograms in other cartouches, he deciphered the names of the native rulers Ramesses and Thutmose.

By now, Champollion knew enough hieroglyphs to confirm that the cartouches on the Rosetta Stone contained the name of one of the Greek rulers of Egypt, Ptolemy V. As Champollion examined more cartouches, he observed that some of the glyphs matched between Ptolemy’s cartouche and other cartouches. Champollion determined that certain glyphs in the cartouches phonetically spelled out the names of certain Greek rulers of Egypt. Using this knowledge and an ingenious reading of ideograms in other cartouches, he deciphered the names of the native rulers Ramesses and Thutmose.

Champollion then began to use this information to decipher the large body of Egyptian hieroglyphs on objects that had been taken to Europe. In 1828 he led a group of artists and architects to Egypt with the goal of drawing pictures of tombs, temples, and monuments and copying down as many hieroglyphic inscriptions as possible. He later translated the hieroglyphs from the drawings. The work of deciphering the hieroglyphs went on after Champollion’s death and continues up to the present day, continually providing new information about life in ancient Egypt.

Today, the Rosetta Stone, the artifact that gave Champollion the clues to crack the code of the ancient Egyptians, is on display in the British Museum in London.