Greece The Persian Wars

Essential Themes

5. Conflict and Cooperation: How has warfare shaped human history?

Introduction: In the 5th century BCE Greek city-states were most often battling one another for land, resources, prestige, and power. When threatened by King Darius the Great and the mighty Persian Empire in 490 BCE, however, they banded together to take on the most powerful army the world had ever seen, and so began the Greco-Persian Wars, a series of battles that stretched over the course of decades.

5. Conflict and Cooperation: How has warfare shaped human history?

Introduction: In the 5th century BCE Greek city-states were most often battling one another for land, resources, prestige, and power. When threatened by King Darius the Great and the mighty Persian Empire in 490 BCE, however, they banded together to take on the most powerful army the world had ever seen, and so began the Greco-Persian Wars, a series of battles that stretched over the course of decades.

The Persian Wars represent one of those truly pivotal moments in History when the past and the future collide. Persia was symbolic of the old ways — a world inhabited by priests and god-kings. Theirs was a world where priests stood guard over knowledge and emperors treated even their highest subjects as slaves. The Greeks symbolized all that was new. They had recently cast off their own god-kings and were just beginning to test a limited concept of political freedom, democracy. At the same time, they were innovating in art, literature and religion, and their philosophies offered new ways to understand the world, unfettered by priestly tradition.

If the underdog Greeks had not been victorious in the Greco-Persian Wars, with the rest of Europe in its sights, Persia might have easily swept past Greece and easily dominated an emerging Latin culture in a very young Rome. Had that happened, our cultural roots, the things we value, indeed, the history we celebrate would be very, very different. Instead, Greek victory led to the "classical age" in Greece, a time that saw advances in art, literature, philosophy, and technology and, for the time, unmatched Greek prosperity. While the Greco-Persian Wars lasted decades and consisted of dozens of battles, for this lesson you will examine the strategies and outcomes of three of the most important contests: Marathon, Thermopylae, and Salamis.

If the underdog Greeks had not been victorious in the Greco-Persian Wars, with the rest of Europe in its sights, Persia might have easily swept past Greece and easily dominated an emerging Latin culture in a very young Rome. Had that happened, our cultural roots, the things we value, indeed, the history we celebrate would be very, very different. Instead, Greek victory led to the "classical age" in Greece, a time that saw advances in art, literature, philosophy, and technology and, for the time, unmatched Greek prosperity. While the Greco-Persian Wars lasted decades and consisted of dozens of battles, for this lesson you will examine the strategies and outcomes of three of the most important contests: Marathon, Thermopylae, and Salamis.

Why did Persia invade Greece?

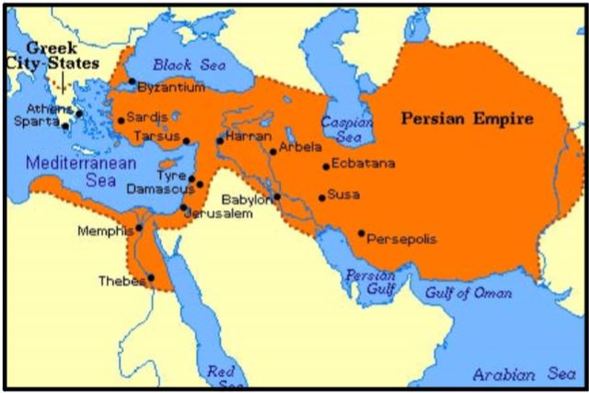

The Battle at Marathon: Persia was a great and huge empire, led by a powerful king and controlled by a highly organized government. In 500 BCE, the Persian Empire led by Darius the Great dominated Greece and everyone else with their size, wealth, and military might. Darius' command stretched from the Mediterranean Sea all the way to the Indus River in Pakistan. At that time, the Greek city-states were not united, and they were tiny compared to the size and population of the vast Persian Empire. Athens, the largest of the Greek city-states only had about 200,000 people living in it.

In 499 BCE, several cities on the coast of modern-day Turkey, cities that had been founded by the Greeks, rebelled against their Persian rulers. Their rebellion is known as the Ionian revolt. Athens sent ships and supplies to help the cities. Even though the Athenian aid did nothing to save the cities, the action made the Persian emperor, Darius, very angry. He decided to teach the Greeks a lesson. In anger Darius gathered together his army and navy and invaded Greece. His sights were set on nothing less than conquest. This set the stage for the battle of Marathon.

In 499 BCE, several cities on the coast of modern-day Turkey, cities that had been founded by the Greeks, rebelled against their Persian rulers. Their rebellion is known as the Ionian revolt. Athens sent ships and supplies to help the cities. Even though the Athenian aid did nothing to save the cities, the action made the Persian emperor, Darius, very angry. He decided to teach the Greeks a lesson. In anger Darius gathered together his army and navy and invaded Greece. His sights were set on nothing less than conquest. This set the stage for the battle of Marathon.

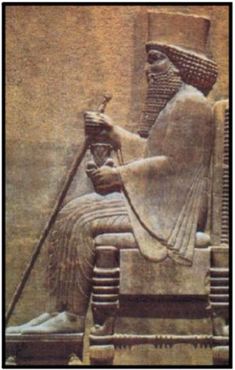

In 490 BCE, Darius the Great, the Persian Emperor pictured at left, brought 600 ships and 20,000 infantry to invade Greece. Because it was big enough to allow his cavalry and their horses room to maneuver, Darius landed his army on the plain of Marathon, up the coast from Athens. At Marathon Darius prepared his attack.

In the hills overlooking Marathon, the Greek army waited and wondered how to handle the Persian army massing on the beaches below. The Greeks knew that if they did not defeat Darius the Persians would not stop fighting until they had conquered all of Greece. Badly outnumbered, Greek commanders in the hills above Marathon sent a messenger named Phidipedes to Sparta to ask for Spartan aid. As the Greeks gathered their army together, they received some disappointing news. The Spartans were not coming. The Spartans were in the midst of a religious holiday that they would not disrupt. (The gods would be angry.)

Brain Box: Aside from the religious festival, do you think there were other motives behind Sparta's refusal to aid the Athenians?

In the hills overlooking Marathon, the Greek army waited and wondered how to handle the Persian army massing on the beaches below. The Greeks knew that if they did not defeat Darius the Persians would not stop fighting until they had conquered all of Greece. Badly outnumbered, Greek commanders in the hills above Marathon sent a messenger named Phidipedes to Sparta to ask for Spartan aid. As the Greeks gathered their army together, they received some disappointing news. The Spartans were not coming. The Spartans were in the midst of a religious holiday that they would not disrupt. (The gods would be angry.)

Brain Box: Aside from the religious festival, do you think there were other motives behind Sparta's refusal to aid the Athenians?

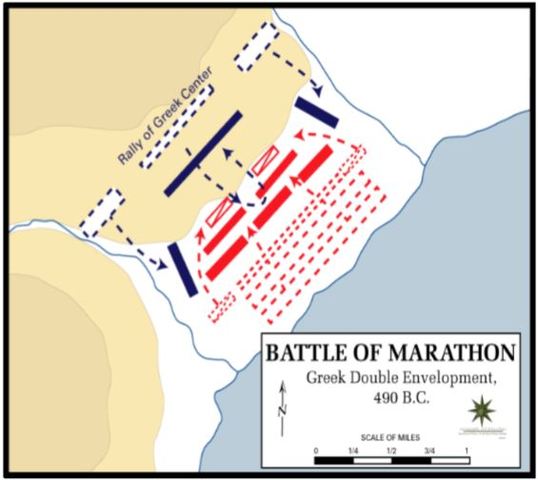

The Greek commander Milatides, counseled boldness. He had a plan. After waiting for days for some hint of activity from the Greek side, the Persians started to load their cavalry and foot soldiers back onto their ships to sail down the coast and attack Athens. Boarding the cavalry first would prove critical to the battle's outcome. It was while the Persians were boarding their ships that Milatides attacked.

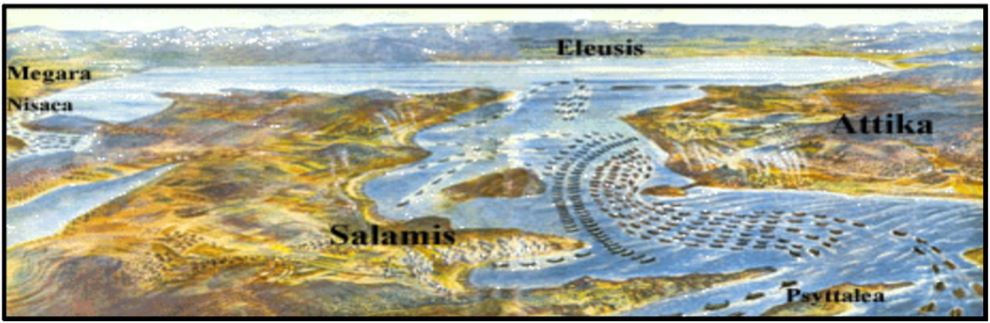

The Greeks had a couple of advantages. First, every Greek soldier wore metal armor. Most of the Persians had leather armor. Second, the Greeks fought using a phalanx. The phalanx was a formation in which soldiers locked shields and formed a wall. Soldiers behind the wall held long spears to stab the enemy.

The Persians had never seen a formation like the phalanx before. The Greeks were well outfitted and the phalanx caused confusion in the Persian army. Should they continue boarding their ships or stop and fight? The Greeks gave them no choice. Attacking at a run, the Greek Phalanx smashed into the Persian army. Attacking at close quarters rendered the Persian archers useless. Aboard their ships, the Persian cavalry was also useless. After a long hard fight, the Greeks drove the Persians back on to their ships. Outnumbered 4 to 1, the Greeks lost 192 soldiers on the beaches of Marathon. By the day's end, however, 6400 Persian forces lay dead. The Greeks weren’t done yet, however. Knowing that in retreat the Persians were heading for Athens, Milatides gathered his army and marched quickly back to the city, a distance of over 26 miles.

The Greeks had a couple of advantages. First, every Greek soldier wore metal armor. Most of the Persians had leather armor. Second, the Greeks fought using a phalanx. The phalanx was a formation in which soldiers locked shields and formed a wall. Soldiers behind the wall held long spears to stab the enemy.

The Persians had never seen a formation like the phalanx before. The Greeks were well outfitted and the phalanx caused confusion in the Persian army. Should they continue boarding their ships or stop and fight? The Greeks gave them no choice. Attacking at a run, the Greek Phalanx smashed into the Persian army. Attacking at close quarters rendered the Persian archers useless. Aboard their ships, the Persian cavalry was also useless. After a long hard fight, the Greeks drove the Persians back on to their ships. Outnumbered 4 to 1, the Greeks lost 192 soldiers on the beaches of Marathon. By the day's end, however, 6400 Persian forces lay dead. The Greeks weren’t done yet, however. Knowing that in retreat the Persians were heading for Athens, Milatides gathered his army and marched quickly back to the city, a distance of over 26 miles.

What happened when Persia invaded Greece?

When Darius sailed with his army to attack what he thought was an undefended Athens, he was shocked to see the Greek army waiting for him on the beach. Despondent, he sailed with his army back to Persia. The Greeks had done the unbelievable, the impossible. They had defeated the Persian Empire. The victory at Marathon was a moral victory for democracy. It shocked Darius that a people would fight for an ideal.

Phidippedes, the same messenger who had previously crossed the 140 miles of the Peloponnesus to ask for Spartan help, ran the 26 miles from Marathon to Athens to bring the news that the Greeks had beaten the Persians, and that the Persians were on their way. In honor of these wonderful accomplishments – victory on the battlefield at Marathon and the successful run from Marathon to Athens to bring the news – today, we use the word “marathon” to describe a long distance race.

Phidippedes, the same messenger who had previously crossed the 140 miles of the Peloponnesus to ask for Spartan help, ran the 26 miles from Marathon to Athens to bring the news that the Greeks had beaten the Persians, and that the Persians were on their way. In honor of these wonderful accomplishments – victory on the battlefield at Marathon and the successful run from Marathon to Athens to bring the news – today, we use the word “marathon” to describe a long distance race.

Review: What advantages did the Greeks have at Marathon?

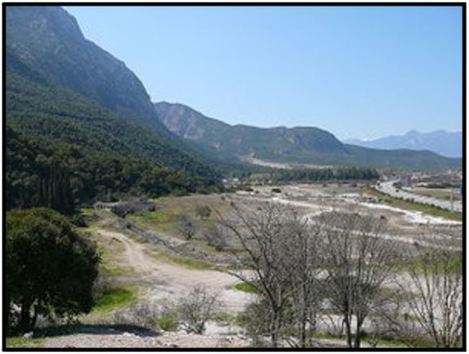

Battle at Thermopylae: Below is a picture of Thermopylae as it appears today. Thermopylae is a narrow pass through the mountains in Greece. By going through the pass, you can reach the plains around Athens.

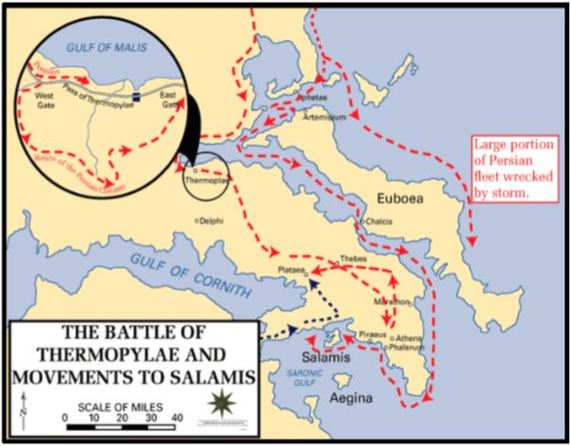

In 480 BCE, ten years had passed since the Persian defeat at Marathon and the Persian Army, led by Darius' son, Xerxes, was on its way back to Greece. Determined to conquer Athens and to teach those upstart Greeks a lesson they would never forget, Xerxes had spent four years gathering 150,000 fighters from all corners of his empire. Transporting them by both land and sea, The Persians were ready to once again attack Athens. To get there, the Persian army had to go through the mountains.

Who is Leonidas?

The Greeks knew that the Persians were coming. You couldn't hide such a large moving army. The Greeks knew that they had to stop the Persians in a place where their huge number of troops would be a disadvantage - in the mountains. King Leonidas, a Spartan general, was in charge of the Greeks. He knew that he could not defeat the entire Persian army. This time, there were just too many of them. But, he had a plan.

In 480 BCE, ten years had passed since the Persian defeat at Marathon and the Persian Army, led by Darius' son, Xerxes, was on its way back to Greece. Determined to conquer Athens and to teach those upstart Greeks a lesson they would never forget, Xerxes had spent four years gathering 150,000 fighters from all corners of his empire. Transporting them by both land and sea, The Persians were ready to once again attack Athens. To get there, the Persian army had to go through the mountains.

Who is Leonidas?

The Greeks knew that the Persians were coming. You couldn't hide such a large moving army. The Greeks knew that they had to stop the Persians in a place where their huge number of troops would be a disadvantage - in the mountains. King Leonidas, a Spartan general, was in charge of the Greeks. He knew that he could not defeat the entire Persian army. This time, there were just too many of them. But, he had a plan.

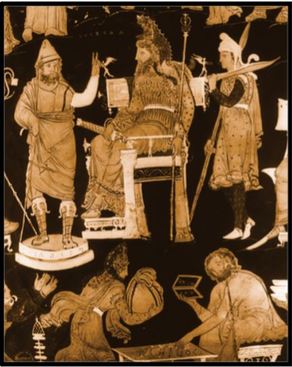

The Persian "Immortals" pictured on the walls of Darius' palace.

The Persian "Immortals" pictured on the walls of Darius' palace.

Leonidas figured that the pass at Thermopylae was so narrow that only a few Persian soldiers at a time could get through. Fighting at over a 20 to 1 disadvantage in the number of troops he had, Leonidas sent most of the Greek army away and kept only a couple of thousand men to guard the pass. The most famous of these were the 300 Spartans of his own army.

Every day, every hour was precious. It allowed the Greeks defending Athens to gather their army together. It allowed them to build more ships for the Athenian navy to use for battle. Leonidas knew he had to stop the Persians at the pass at Thermopylae for as long as possible. And stop them he did.

One day, two days, how long could the Greeks hold out? It seemed as if no one could defeat the Spartans. The Persians sent in their elite troops, "the immortals." The immortals had earned their name for their skill and their bravery in combat. The number of "immortals" was so great that when they swarmed the battlefield and one "immortal" fell another immediately took his place. Even with his fighting elites engaged in battle, however, Xerxes' troops made little progress against the Greeks. How could the Persian army ever get through the pass? The answer appeared in their midst. A traitor from the Greek army named Ephialtes showed the Persians a little known path through the mountains and around the Greeks. So great was the treachery that, in common usage today, the word ephialtes means "nightmare."

When Leonidas discovered the betrayal, he knew his troops would soon be surrounded by the Persians. With the fate of the Greeks at Thermopylae sealed, the Persians sent a commander to ask if the Spartans would like to surrender. The Spartans replied, "Never!" In disbelief, the Persian commander pointed to his archers and told Leonidas that if he did not surrender arrows would be launched in such great quantity that they would black out the sun. To which, the Spartan commander is famously said to have replied, "Then we shall fight in the shade."

Every day, every hour was precious. It allowed the Greeks defending Athens to gather their army together. It allowed them to build more ships for the Athenian navy to use for battle. Leonidas knew he had to stop the Persians at the pass at Thermopylae for as long as possible. And stop them he did.

One day, two days, how long could the Greeks hold out? It seemed as if no one could defeat the Spartans. The Persians sent in their elite troops, "the immortals." The immortals had earned their name for their skill and their bravery in combat. The number of "immortals" was so great that when they swarmed the battlefield and one "immortal" fell another immediately took his place. Even with his fighting elites engaged in battle, however, Xerxes' troops made little progress against the Greeks. How could the Persian army ever get through the pass? The answer appeared in their midst. A traitor from the Greek army named Ephialtes showed the Persians a little known path through the mountains and around the Greeks. So great was the treachery that, in common usage today, the word ephialtes means "nightmare."

When Leonidas discovered the betrayal, he knew his troops would soon be surrounded by the Persians. With the fate of the Greeks at Thermopylae sealed, the Persians sent a commander to ask if the Spartans would like to surrender. The Spartans replied, "Never!" In disbelief, the Persian commander pointed to his archers and told Leonidas that if he did not surrender arrows would be launched in such great quantity that they would black out the sun. To which, the Spartan commander is famously said to have replied, "Then we shall fight in the shade."

What advantages did the Greeks have at Thermopylae?

The Persians attacked, the Spartans defended. Again the Spartans were victorious. The Persians were tired of this so, as promised, they called in all their archers and started firing arrows at the Spartans. One by one the Spartans were dying from the thousands of arrows raining down upon them. There was only one thing to do. Attack! They formed a phalanx and attacked.

The Persians continued firing arrows until, finally, all 300 Spartans lay dead on the ground. Because the Spartans had held the pass for as long as they did, their sacrifice allowed the Greeks in Athens to prepare for the arrival of the Persians. By the time the Persian troops entered Athens, the city had been evacuated. Xerxes discovered a ghost town filled with only the echoes of his own troops' boots on the ground. Because of their act of heroism at Thermopylae Pass, Sparta is still remembered and honored today.

The Persians continued firing arrows until, finally, all 300 Spartans lay dead on the ground. Because the Spartans had held the pass for as long as they did, their sacrifice allowed the Greeks in Athens to prepare for the arrival of the Persians. By the time the Persian troops entered Athens, the city had been evacuated. Xerxes discovered a ghost town filled with only the echoes of his own troops' boots on the ground. Because of their act of heroism at Thermopylae Pass, Sparta is still remembered and honored today.

The Battle at Salamis: When the Persian king, Xerxes, invaded Greece in the spring of 480 BCE, he did so at the head of a vast army. Once the Spartan force at Thermopylae had been defeated, his route by land to Athens was virtually undefended.

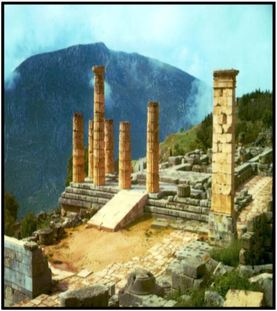

In a near panic over what to do, the Athenians sought the wisdom of the Oracle of Delphi. The Greeks used the word “oracle” to describe the person through whom the gods could speak, the place or temple where the gods could speak, and the answer the gods would give. So, when speaking to the gods, the word “oracle” is used to describe the person, the place, and the answer. The remains of the Oracle at Delphi are pictured to the right.

In a near panic over what to do, the Athenians sought the wisdom of the Oracle of Delphi. The Greeks used the word “oracle” to describe the person through whom the gods could speak, the place or temple where the gods could speak, and the answer the gods would give. So, when speaking to the gods, the word “oracle” is used to describe the person, the place, and the answer. The remains of the Oracle at Delphi are pictured to the right.

Who is Themistocles?

When asked what Athens should do, the Oracle responded, "Though all else shall be taken, Zeus, the all seeing, grants that the wooden wall only shall not fail." Athens had a stone wall. Arguments in Athens raged as to what this "wooden wall" could mean. Many believed it to be the thorn bushes surrounding the Acropolis.

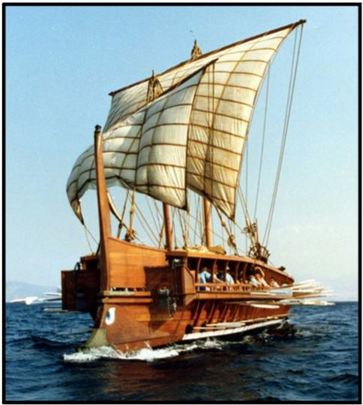

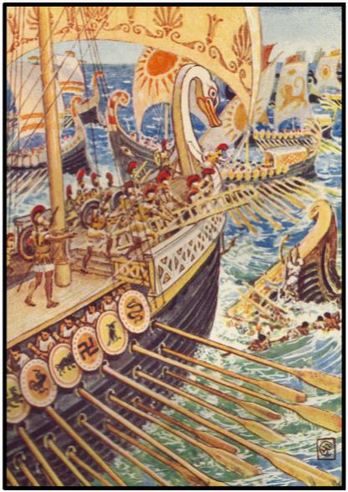

The Athenian general, Themistocles, had an answer of his own. The wooden wall, he argued, was the fleet of naval ships , including the speedy triremes like the one pictured at left, that Athenians had spent the last few years hurriedly building. Themistocles' interpretation won the day and he immediately gave the order for Athens itself to be abandoned.

The Persians had lost two major battles to the upstart Greeks. On their march toward Athens, they were not about to lose a third. They were determined to win, and to win big. In addition to his land forces, Xerxes, the leader of the Persian Army, packed 1200 ships with well-equipped fighting men, and set sail for Athens. 1200 ships! Can you imagine? What a sight that must have been!

When asked what Athens should do, the Oracle responded, "Though all else shall be taken, Zeus, the all seeing, grants that the wooden wall only shall not fail." Athens had a stone wall. Arguments in Athens raged as to what this "wooden wall" could mean. Many believed it to be the thorn bushes surrounding the Acropolis.

The Athenian general, Themistocles, had an answer of his own. The wooden wall, he argued, was the fleet of naval ships , including the speedy triremes like the one pictured at left, that Athenians had spent the last few years hurriedly building. Themistocles' interpretation won the day and he immediately gave the order for Athens itself to be abandoned.

The Persians had lost two major battles to the upstart Greeks. On their march toward Athens, they were not about to lose a third. They were determined to win, and to win big. In addition to his land forces, Xerxes, the leader of the Persian Army, packed 1200 ships with well-equipped fighting men, and set sail for Athens. 1200 ships! Can you imagine? What a sight that must have been!

What advantages did the Greeks have at Salamis?

|

Rather than commanding his men personally, Xerxes ordered a comfortable chair to be placed on a hilltop where he could watch the battle in the far distance, as if it were entertainment to be staged for his amusement.

The ancient Greeks did not need spies to tell them that the Persians would be back in great numbers. They knew the Persians would be back. But the ancient Greeks were fighters. They would rather die than lose. They would rather win than die. They knew they had some advantages, so they planned on how best to use those advantages. |

Greek Advantage: Athletic Ability. For one thing, the Greeks could swim. The Persians had already demonstrated that if they fell in the water, they drowned. Most could not swim to shore or swim to another Persian boat to save their own lives if they fell into the water.

Using this advantage, the Greeks practiced a new maneuver. The plan was to move quickly alongside an enemy ship. Once there, at the last second, they practiced raising their oars vertically, fast and hard, to break the enemy’s oars. If they broke them, the ship would be stuck. The men could not row away until they were given new oars. The men could not swim away because they could not swim. Basically, they would be sitting ducks. It was a very smart plan.

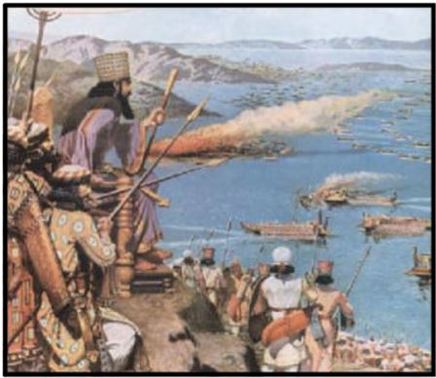

Greek Advantage: Knowledge. The Greeks had the advantage of fighting on their home turf. They knew the waterways. They knew the currents. They decided that if they had smaller ships that were faster and easier to maneuver, being incredibly outnumbered might not matter as much, especially if the enemy ship was stuck and they were free to move around.

Athens used money from their brand new silver mines to build as many ships as they could before the Persians arrived at Salamis. They designed a new ship called a trireme. A trireme is a ship with three levels of rowers. This gave speed to their ships and strength to their battle plan of enemy oar breaking. Athens built about 200 triremes. Together, the other Greek city-states supplied another 200 triremes for the battle of Salamis.

Using this advantage, the Greeks practiced a new maneuver. The plan was to move quickly alongside an enemy ship. Once there, at the last second, they practiced raising their oars vertically, fast and hard, to break the enemy’s oars. If they broke them, the ship would be stuck. The men could not row away until they were given new oars. The men could not swim away because they could not swim. Basically, they would be sitting ducks. It was a very smart plan.

Greek Advantage: Knowledge. The Greeks had the advantage of fighting on their home turf. They knew the waterways. They knew the currents. They decided that if they had smaller ships that were faster and easier to maneuver, being incredibly outnumbered might not matter as much, especially if the enemy ship was stuck and they were free to move around.

Athens used money from their brand new silver mines to build as many ships as they could before the Persians arrived at Salamis. They designed a new ship called a trireme. A trireme is a ship with three levels of rowers. This gave speed to their ships and strength to their battle plan of enemy oar breaking. Athens built about 200 triremes. Together, the other Greek city-states supplied another 200 triremes for the battle of Salamis.

Greek Advantage: Cleverness. 400 ships was a lot, but the Greeks knew that it would not be enough in an open fight since their Greek spies had reported that the Persians planned to bring 1200 ships loaded with soldiers. The Greeks needed more. The clever Athenians added a couple of things to help bring the odds a bit more into their favor.

The Greeks increased the strength of their boats. They added a ram (a built up, strengthened point) to the bow (to the front) of their ships, to help them ram and sink the enemy ships.

The Greeks used the technique of misinformation. The Greeks sent someone who was pretending to be a traitor into the Persian army. This “traitor” told the Persians that the Greeks were going to pretend to retreat through the Gulf of Salamis, but the Greek fleet would be hidden on the other side, ready for a surprise attack.

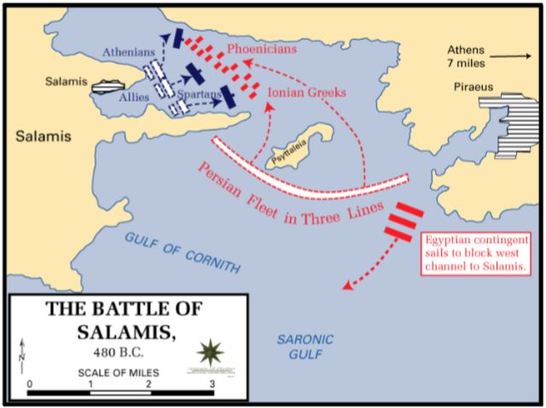

Since the Persian General thought he knew the Greek plan, he created a plan of his own. Based on the misinformation he had received from the Greek “traitor,” his plan was to send in all his ships at once and overwhelm the Greeks through sheer numbers, putting 3 or 4 of his ships against every Greek ship, before the Greeks could retreat through the Gulf of Salamis, to join the rest of their fleet. Unfortunately for the Persians, that’s exactly what the Greeks wanted them to do. For the Greek battle plan to work, they needed the Persian ships to be close together.

The Greeks increased the strength of their boats. They added a ram (a built up, strengthened point) to the bow (to the front) of their ships, to help them ram and sink the enemy ships.

The Greeks used the technique of misinformation. The Greeks sent someone who was pretending to be a traitor into the Persian army. This “traitor” told the Persians that the Greeks were going to pretend to retreat through the Gulf of Salamis, but the Greek fleet would be hidden on the other side, ready for a surprise attack.

Since the Persian General thought he knew the Greek plan, he created a plan of his own. Based on the misinformation he had received from the Greek “traitor,” his plan was to send in all his ships at once and overwhelm the Greeks through sheer numbers, putting 3 or 4 of his ships against every Greek ship, before the Greeks could retreat through the Gulf of Salamis, to join the rest of their fleet. Unfortunately for the Persians, that’s exactly what the Greeks wanted them to do. For the Greek battle plan to work, they needed the Persian ships to be close together.

Greek Advantage: Courage. The ancient Greeks had the wonderful ability to stick to a plan. It took great courage to stick to this plan. But they did. When the battle started, the Greeks pretended to retreat in front of the Persians as planned, just as the “traitor” had said they would. However, the rest of the Greek fleet was not hidden on the other side of the Gulf of Salamis. The rest of the fleet was hidden on this side, behind islands and in the many small rivers and channels that lined the Straits of Salamis.

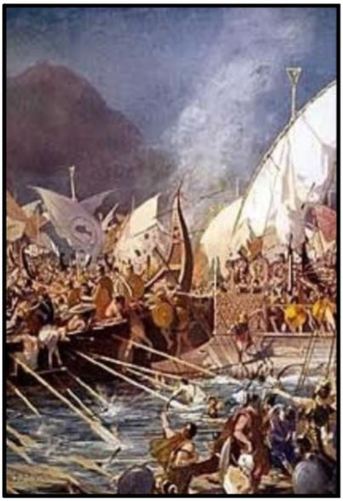

As the Persian fleet entered the Straits of Salamis, Xerxes' naval commanders turned to face the Greeks, forming three impressive lines of Persian ships. The Greek fleet stood firm for a minute. Then, using the speed of their three levels of rowers, they exploded toward the Persian fleet. Panicked, the front line of Persian boats flinched and backed into the line of ships behind them. In their confusion, the Persian ships created a tangled web of oars that made many boats easy targets for the fast, nimble Greek fleet. It was then that Greek ships poured in from all side, from the channels, and from behind the islands.

The Persians were surrounded. The Greek fleet slammed against the sides of the Persian ships, as they had practiced. At the last second, they slapped their oars straight up with great strength and speed, cracking Persian oars into bits. Many of the Persian ships had so many cracked oars that the men could not row away. They could not swim away. They were stuck.

As the Persian fleet entered the Straits of Salamis, Xerxes' naval commanders turned to face the Greeks, forming three impressive lines of Persian ships. The Greek fleet stood firm for a minute. Then, using the speed of their three levels of rowers, they exploded toward the Persian fleet. Panicked, the front line of Persian boats flinched and backed into the line of ships behind them. In their confusion, the Persian ships created a tangled web of oars that made many boats easy targets for the fast, nimble Greek fleet. It was then that Greek ships poured in from all side, from the channels, and from behind the islands.

The Persians were surrounded. The Greek fleet slammed against the sides of the Persian ships, as they had practiced. At the last second, they slapped their oars straight up with great strength and speed, cracking Persian oars into bits. Many of the Persian ships had so many cracked oars that the men could not row away. They could not swim away. They were stuck.

Once the ships were stuck, the Greek fleet began ramming ships, sinking the Persians, but remaining afloat themselves, thanks to the build up front end of their boats. Accounts say about 200 of the Persian ships were sunk at Salamis. The Greeks boarded other ships, killing the men aboard. Only about 200 ships of the original 1200 ships sent by the Persians escaped.

The Persian emperor, Xerxes, had placed his throne on top of hill so he could watch the great victory of his men. Instead, he wept at the loss of so many men and ships. The Persians took their remaining ships and their army and retreated to Northern Greece. Xerxes left an army of about 80,000 men in Northern Greece, and took the rest of his men home to Persia.

The Persian emperor, Xerxes, had placed his throne on top of hill so he could watch the great victory of his men. Instead, he wept at the loss of so many men and ships. The Persians took their remaining ships and their army and retreated to Northern Greece. Xerxes left an army of about 80,000 men in Northern Greece, and took the rest of his men home to Persia.

|

Greek Advantage: Teamwork. The Spartans gathered together an army from the rest of the Greek city-states and met the Persians at Platea for one of the last Persian War battles. The Persian army was defeated there and destroyed. Meanwhile the Athenians had gathered together the Greek fleet and set off for the coast of Asia-minor. In 477 BCE, they destroyed what was left of the Persian navy at Mycale.

Victory: The incredible had happened. The tiny city-states of Greece had beaten the huge Persian Empire. The pride that the ancient Greeks felt over winning this war started a new age – the Golden Age of Greece. |