MAYA SOCIETY

Essential Themes

Beliefs: Why do people live the way they do?

Government: How do humans organize their societies, and why do they organize them the way they do?

Beliefs: Why do people live the way they do?

Government: How do humans organize their societies, and why do they organize them the way they do?

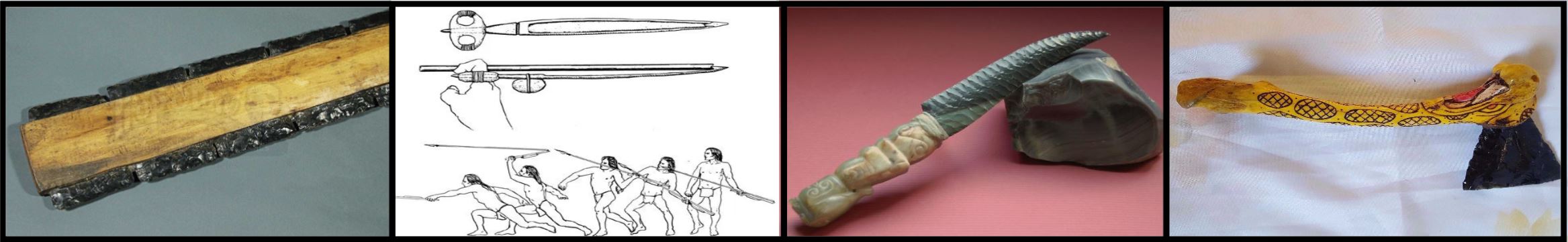

SOCIAL CLASSES

The Maya had a class society. As in other mesoamerican cultures, an individual’s daily life depended on their social class. There were slaves, peasants, artisans & merchants, nobility, priests, and leaders. There were also warriors. The highest class was made up of the nobility. Aside from the king, nobles included priests, scribes, government officials, and elite warriors. The middle class was made up of the craftsmen, traders, weavers, potters, and other warriors. At the bottom of the social order were farmers, other workers, and slaves.

The Maya had a class society. As in other mesoamerican cultures, an individual’s daily life depended on their social class. There were slaves, peasants, artisans & merchants, nobility, priests, and leaders. There were also warriors. The highest class was made up of the nobility. Aside from the king, nobles included priests, scribes, government officials, and elite warriors. The middle class was made up of the craftsmen, traders, weavers, potters, and other warriors. At the bottom of the social order were farmers, other workers, and slaves.

As you learned in your last lesson, The Maya social structure was fairly rigid without much room for mobility, even from one generation to the next. From the king down, for instance, the job of a Maya man was inherited from his father. If your father was a king, you would inherit the throne. If your father was a farmer, you were a farmer. If your father made bricks, you made bricks. There were some exceptions, but they were rare. There was somewhat more flexibility for women. Some women were involved in government, economics, and religion. At the same time, however, they were still responsible for taking care of the children and managing the home, just like their mothers.

SLAVES

To understand the Maya social order, you need to begin at the bottom. Slaves were the lowest class in Maya society. They were usually orphans, war prisoners, criminals, or the children of slaves. Although they weren't necessarily mistreated by their owners, slaves still had no rights or privileges in Maya society. Basically, a slave's only function in society was to do all of the manual labor. Because of that, Maya society depended on them. Slaves worked in the homes of noble families. Some slaves cared for the children. Some cleaned the house. Still others worked in the fields. Additionally, slaves helped with the construction of the great Maya temples like the one pictured at right. They were also the ones most frequently used for the Maya ritual of human sacrifice.

To understand the Maya social order, you need to begin at the bottom. Slaves were the lowest class in Maya society. They were usually orphans, war prisoners, criminals, or the children of slaves. Although they weren't necessarily mistreated by their owners, slaves still had no rights or privileges in Maya society. Basically, a slave's only function in society was to do all of the manual labor. Because of that, Maya society depended on them. Slaves worked in the homes of noble families. Some slaves cared for the children. Some cleaned the house. Still others worked in the fields. Additionally, slaves helped with the construction of the great Maya temples like the one pictured at right. They were also the ones most frequently used for the Maya ritual of human sacrifice.

COMMONERS

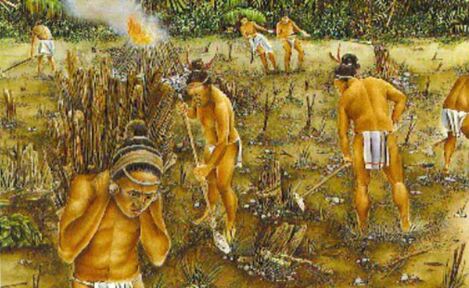

Most Maya lived in the lower classes and most of the lower class was made up of commoners. Because the Maya depended on agriculture for food and for trade, most commoners were farmers during the growing season. Once crops were harvested, farmers often went to work building the pyramids and temples found in their beautiful cities. While some commoners might also work as servants to the noble class, as porters, or in the limestone quarries cutting stone for the numerous Maya building projects, most commoners were farmers who passed down their life of hard labor from one generation to the next. Whether on the farm, at a construction site, or at one of their other occupations, life for commoners involved a lot of hard labor.

The Maya did not have metal tools or pack animals such as horses or oxen to help with the plowing, so fathers and sons worked their land mostly by hand. The use of stone axes helped a little and when a sharp edge was needed they fashioned cutting tools from obsidian or flint. Wives and daughters cooked, cleaned, and sewed. Girls babysat their youngest siblings. Women carried goods in baskets on their heads from the fields and to market, and they helped in the fields when necessary.

Most Maya lived in the lower classes and most of the lower class was made up of commoners. Because the Maya depended on agriculture for food and for trade, most commoners were farmers during the growing season. Once crops were harvested, farmers often went to work building the pyramids and temples found in their beautiful cities. While some commoners might also work as servants to the noble class, as porters, or in the limestone quarries cutting stone for the numerous Maya building projects, most commoners were farmers who passed down their life of hard labor from one generation to the next. Whether on the farm, at a construction site, or at one of their other occupations, life for commoners involved a lot of hard labor.

The Maya did not have metal tools or pack animals such as horses or oxen to help with the plowing, so fathers and sons worked their land mostly by hand. The use of stone axes helped a little and when a sharp edge was needed they fashioned cutting tools from obsidian or flint. Wives and daughters cooked, cleaned, and sewed. Girls babysat their youngest siblings. Women carried goods in baskets on their heads from the fields and to market, and they helped in the fields when necessary.

|

Maya farming families started their day early. Men and boys would head to the fields or the latest building site and women went to work in their homes, cooking, grinding corn, raising the children, tending gardens, checking beehives and weaving cloth for their own clothes and for the market. Commoners worked hard but ate well. Breakfast consisted of hot corn porridge flavored with either chilies or honey. While working during

|

|

the day, men and boys would eat a dumpling made of corn and filled with vegetables and meat. At home after work, the family gathered for their main meal, stuffing tortillas with vegetables, along with meat or fish when they had it. With another day of hard work ahead of them the following dawn, everyone settled down to sleep as soon as it got dark.

Life wasn’t all work for Maya commoners, however. At least every month, a religious festival took place in the city and everyone would go to sing and dance and to worship their many gods. Festivals also meant feasts of delicious foods and, along with the rest of their community, commoners might watch a game of Pok-a-Tok. And, as children do everywhere, Maya children played with toys. To the left, is a toy jaguar on wheels and two animal-shaped whistles. Seeing wheeled toys, doesn't it make you wonder why the wheel was not more widely used in Mesoamerica?

Life wasn’t all work for Maya commoners, however. At least every month, a religious festival took place in the city and everyone would go to sing and dance and to worship their many gods. Festivals also meant feasts of delicious foods and, along with the rest of their community, commoners might watch a game of Pok-a-Tok. And, as children do everywhere, Maya children played with toys. To the left, is a toy jaguar on wheels and two animal-shaped whistles. Seeing wheeled toys, doesn't it make you wonder why the wheel was not more widely used in Mesoamerica?

ARTISANS

In early Maya times, there was probably little difference between nobles and commoners. The growth of Maya cities, however, changed that. As trade between cities grew and became more important, groups of people formed to manage important building projects in the cities and to create the goods for trade. These people made up the middle class in Maya society. The Maya middle class included artisans, merchants, minor government officials, warriors, and some scribes. Basically, all of these people worked for the government or in commerce.

In early Maya times, there was probably little difference between nobles and commoners. The growth of Maya cities, however, changed that. As trade between cities grew and became more important, groups of people formed to manage important building projects in the cities and to create the goods for trade. These people made up the middle class in Maya society. The Maya middle class included artisans, merchants, minor government officials, warriors, and some scribes. Basically, all of these people worked for the government or in commerce.

Maya artisans had a slightly easier life than the hard, physical labor demanded from the commoners who worked on the farms. While artisans were still considered commoners, rather than heading off to the fields, they spent their days creating beautiful items such as jewelry, textiles, pottery, and feather cloaks and headdresses. Although the woven textiles and feathered goods created by the Maya artisans decayed over time and are no longer around, the stone carvings and jewelry that remain are a bold statement about the skills of the Maya artisans.

Jade funeral masks were a very particular type of craft work. Above is the funeral mask for Pa'kal the Great, King of Palenque.

Jade funeral masks were a very particular type of craft work. Above is the funeral mask for Pa'kal the Great, King of Palenque.

All living under one roof, Maya families included not only mothers, fathers and children, but also aunts, uncles and grandparents. Because children typically inherited their jobs from their parents, within Maya communities you could see entire families of artisans involved in the same craft work, with each family member playing a part in creating goods for the market or as tribute to the king.

While families of artisans might live in slightly bigger houses, the pattern of their daily life was much the same as that of the farmers. Like the farmers, artisans rose early to begin a long day working at their craft. Breakfast was usually the same as the farmer’s breakfast, but wealthier artisans might even have a cup of hot chocolate, a drink usually reserved for the nobility.

While families of artisans might live in slightly bigger houses, the pattern of their daily life was much the same as that of the farmers. Like the farmers, artisans rose early to begin a long day working at their craft. Breakfast was usually the same as the farmer’s breakfast, but wealthier artisans might even have a cup of hot chocolate, a drink usually reserved for the nobility.

Standing an impressive 12 feet high, these two stelae at Quirigia tell the Maya creation story in great detail.

Standing an impressive 12 feet high, these two stelae at Quirigia tell the Maya creation story in great detail.

After breakfast, work began. Carvers might go to a new temple complex to begin work on a stele, a great stone column that celebrated the king’s life and deeds or important events in the life of the community. Feather workers might go to the market to see if hunters or rare bird breeders had any feathers to sell. Those who made jewelry or pottery probably worked at a home studio or in a common building dedicated to their craft.

While most of the goods produced by Maya artisans were for the noble class and royalty, artisans could also sell their goods at market with the profit going to the family. Once they had paid tribute to their king and taxes to their community, artisans could use the remainder of what they earned to improve their lives. Usually that meant improvements to their home, better food, or fancier jewelry or clothing.

MERCHANTS

Farming formed the core of Maya civilization. With the growth of large cities during the Classic Period, however, trade became equally important. Indeed, trade was so essential to the Maya that they even had a god devoted to merchants and traders. The name of the Maya god of trade was Bolon Yookte'K'Oh.

Prior to the growth of cities, most Maya lived in small villages that were easy to sustain with the food grown and with the work done by the villagers themselves. As cities grew and the populations stretched into the tens of thousands, the only way to meet local needs was by trading with other villages and cities.

While most of the goods produced by Maya artisans were for the noble class and royalty, artisans could also sell their goods at market with the profit going to the family. Once they had paid tribute to their king and taxes to their community, artisans could use the remainder of what they earned to improve their lives. Usually that meant improvements to their home, better food, or fancier jewelry or clothing.

MERCHANTS

Farming formed the core of Maya civilization. With the growth of large cities during the Classic Period, however, trade became equally important. Indeed, trade was so essential to the Maya that they even had a god devoted to merchants and traders. The name of the Maya god of trade was Bolon Yookte'K'Oh.

Prior to the growth of cities, most Maya lived in small villages that were easy to sustain with the food grown and with the work done by the villagers themselves. As cities grew and the populations stretched into the tens of thousands, the only way to meet local needs was by trading with other villages and cities.

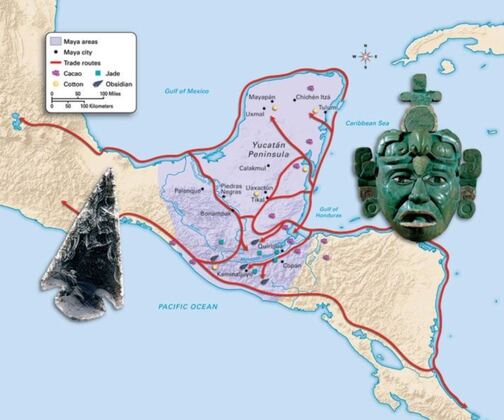

Well-established trade routes linked Maya cities.

Well-established trade routes linked Maya cities.

Maya merchants traded two kinds of goods, items for everyday use and luxury items. Everyday use items included things such as salt, which was especially important in their hot climate, food, clothing and tools. Luxury items were the things that royalty and nobles used to show off their wealth and power. Those items included jade, gold, beautiful ceramics, jewelry and feather works.

Luxury items often followed longer trade routes. Long distance traders took their goods along established trade routes that stretched from Mexico in the north, through Central America and even down to South America. Maya traders even reached Cuba and the islands of the Caribbean by traveling in canoes so large that they could hold up to twenty people plus trade goods.

When talking about Maya trade, it is important to remember that they did not have money. Therefore "trade" was, literally, just that - trade. Maya merchants exchanged items that they had in surplus for items that they needed.

Not everything that was traded, however, was of equal value. In fact, the more rare, sought after, luxurious items could be worth considerably more than common items. For instance, just one ounce of Quetzal feathers could get you fifty pounds of corn, one ounce of cacao beans could get you two pounds of corn, and one ounce of gold could get you twenty pounds of corn. Corn was traded a lot!

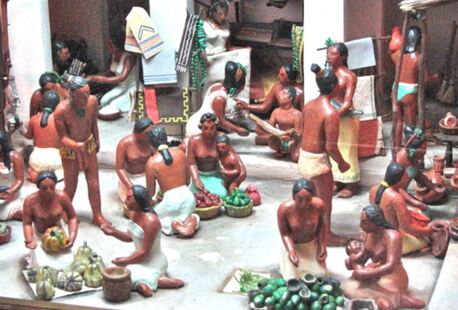

Larger cities required food to be brought into markets from outside of the city. Most food was grown locally, but what wasn’t grown nearby had to be brought in through trade with other city-states or tribute to a city’s king. Most food was traded regionally or in local markets. Food items brought to the market included turkeys, ducks, dogs, fish, honey, beans and fruit.

Luxury items often followed longer trade routes. Long distance traders took their goods along established trade routes that stretched from Mexico in the north, through Central America and even down to South America. Maya traders even reached Cuba and the islands of the Caribbean by traveling in canoes so large that they could hold up to twenty people plus trade goods.

When talking about Maya trade, it is important to remember that they did not have money. Therefore "trade" was, literally, just that - trade. Maya merchants exchanged items that they had in surplus for items that they needed.

Not everything that was traded, however, was of equal value. In fact, the more rare, sought after, luxurious items could be worth considerably more than common items. For instance, just one ounce of Quetzal feathers could get you fifty pounds of corn, one ounce of cacao beans could get you two pounds of corn, and one ounce of gold could get you twenty pounds of corn. Corn was traded a lot!

Larger cities required food to be brought into markets from outside of the city. Most food was grown locally, but what wasn’t grown nearby had to be brought in through trade with other city-states or tribute to a city’s king. Most food was traded regionally or in local markets. Food items brought to the market included turkeys, ducks, dogs, fish, honey, beans and fruit.

In addition to food stuffs, Maya merchants also traded both raw materials and manufactured goods. Raw goods included jade, copper, gold, granite, marble, limestone, and wood. Manufactured goods included textiles, especially beautifully embroidered cloth, clothing, feather capes and headdresses, paper, furniture, jewelry, toys and weapons. Specialists such as architects, mathematicians, scribes and engineers sold their services at the market as well.

How did Maya warriors prepare for battle?

The clay figures above show different aspects of a typical warriors "kit." Notice the heavy cloth armor on the left, and the "noisemakers" attached to the shield on the right.

The clay figures above show different aspects of a typical warriors "kit." Notice the heavy cloth armor on the left, and the "noisemakers" attached to the shield on the right.

Warriors

For years, it was believed that the Maya were mostly peaceful, fighting only occasional wars for captives to be used in human sacrifice. Evidence from more recent archaeological digs, however, suggests that during the late Classic Period (600-900 CE) war was a nearly constant state of affairs for Maya kings who were after more land, natural resources, and the control of trade networks.

Because of the nearly constant warfare that evolved, well-trained warriors were important to the Maya way of life and the job of warrior was highly respected. The Maya were fierce warriors. Before they went into battle, warriors created a confidence-building shield. This was a round, flat circle, covered with pictures that represented all the wonderful things they had accomplished and all the battles they had won. Before a big battle, warriors would dance around holding their shields, accompanied by noisemakers, to psyche themselves up for battle.

For years, it was believed that the Maya were mostly peaceful, fighting only occasional wars for captives to be used in human sacrifice. Evidence from more recent archaeological digs, however, suggests that during the late Classic Period (600-900 CE) war was a nearly constant state of affairs for Maya kings who were after more land, natural resources, and the control of trade networks.

Because of the nearly constant warfare that evolved, well-trained warriors were important to the Maya way of life and the job of warrior was highly respected. The Maya were fierce warriors. Before they went into battle, warriors created a confidence-building shield. This was a round, flat circle, covered with pictures that represented all the wonderful things they had accomplished and all the battles they had won. Before a big battle, warriors would dance around holding their shields, accompanied by noisemakers, to psyche themselves up for battle.

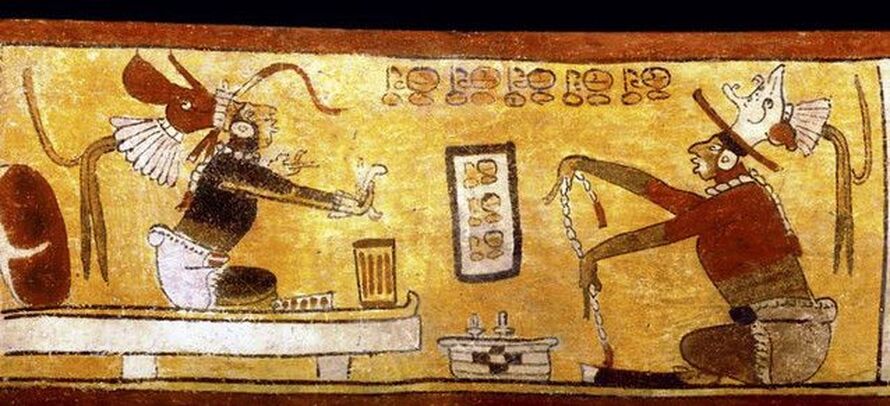

The weapons used by Maya warriors typically fell into two categories. Long distance weapons included spears, blow guns, slings and, later, the bow and arrow. Because the warrior’s goal was more often to capture than to kill, however, the more commonly used weapons were designed for hand to hand combat. Those weapons included clubs with obsidian lined sides that were good for both thumping and cutting, knives, and axes. The axes were typically double sided with one cutting edge and one blunt edge used to stun their opponent.

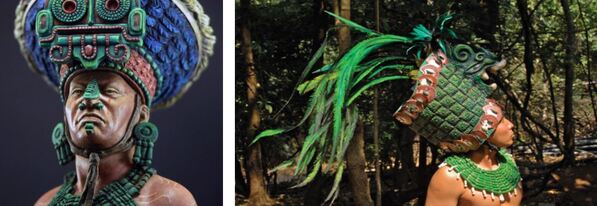

Notice this Maya noble's fancy hat, earrings, necklace, and large feather cape draped over his right arm.

Notice this Maya noble's fancy hat, earrings, necklace, and large feather cape draped over his right arm.

Nobles

The noble class of was the smallest of any of the the Maya social classes, but they were far more wealthy and powerful. Basically, the nobles were people who had royal blood but were not the king. They performed some of the most important Maya jobs. They were the priests and government officials, the court officers and town rulers and administrators, the scribes and tax collectors, as well as the military leaders. Such important work was always kept in the royal family and passed down to their children.

According to Maya beliefs, nobles filled a space somewhere between gods and humans. With that elevated social standing, they were expected to serve both. Because of their status as go-betweens for the Maya gods and humans, nobles received more material benefits than lower class Maya. Rather than single room huts, they lived in large stone house in the center of Maya cities. Their diet was similar to other classes, but they probably ate more meat and enjoyed a delicious, frothy chocolate drink daily. In return for the benefits they received, nobles made regular offerings to the gods, offerings that included their own blood. They used stingray spines or thorns to pierce their ears or tongue and they considered doing so an honor. They would squeeze their blood onto strips of paper, which were then burnt in an offering to the gods.

The noble class of was the smallest of any of the the Maya social classes, but they were far more wealthy and powerful. Basically, the nobles were people who had royal blood but were not the king. They performed some of the most important Maya jobs. They were the priests and government officials, the court officers and town rulers and administrators, the scribes and tax collectors, as well as the military leaders. Such important work was always kept in the royal family and passed down to their children.

According to Maya beliefs, nobles filled a space somewhere between gods and humans. With that elevated social standing, they were expected to serve both. Because of their status as go-betweens for the Maya gods and humans, nobles received more material benefits than lower class Maya. Rather than single room huts, they lived in large stone house in the center of Maya cities. Their diet was similar to other classes, but they probably ate more meat and enjoyed a delicious, frothy chocolate drink daily. In return for the benefits they received, nobles made regular offerings to the gods, offerings that included their own blood. They used stingray spines or thorns to pierce their ears or tongue and they considered doing so an honor. They would squeeze their blood onto strips of paper, which were then burnt in an offering to the gods.

Of all their fancy clothes, a point of special pride for Maya nobles was what they wore atop their head.

Of all their fancy clothes, a point of special pride for Maya nobles was what they wore atop their head.

In addition to their nice homes and larger meals, Maya nobles also loved wearing fancy clothes and elaborate jewelry. In fact, both men and women nobles took great pride in their personal appearance. They pierced their ears. They covered their bodies with tattoos. They painted their bodies. They loved to have fancy, colorful embroidery added to their clothing. And, they loved jewelry. Combined with Maya laws prohibiting commoners from wearing the type of clothes worn by nobles, their fashionable extravagance made Maya nobles easily recognizable.

For the Maya, just as in other ancient civilizations, the life of a noble was easier than for a commoner. A noble's life wasn't without drawbacks, however. If a noble was captured in a war, they were far more likely to be tortured and sacrificed to the gods. While captured commoners could also be sacrificed, they were more likely to end up as slaves.

For the Maya, just as in other ancient civilizations, the life of a noble was easier than for a commoner. A noble's life wasn't without drawbacks, however. If a noble was captured in a war, they were far more likely to be tortured and sacrificed to the gods. While captured commoners could also be sacrificed, they were more likely to end up as slaves.

Priests were involved in nearly every aspect of Maya life.

Priests were involved in nearly every aspect of Maya life.

Priests

Religion was at the heart of nearly all Maya activities. Because of that, Maya priests were second in importance, behind only Maya kings in their social order.

Maya priests were the most highly educated of all Maya. They were considered the keepers of knowledge. They learned to read and write and taught those skills to the sons of nobles. They also studied astronomy and astrology and used the complex Maya calendar to advise on everything from when to plant crops to prophecies for kings, nobles and commoners. Priests kept track of family lines of succession, especially for Maya kings. With that combination of skills, you might say that priests were also Maya historians.

Religion was at the heart of nearly all Maya activities. Because of that, Maya priests were second in importance, behind only Maya kings in their social order.

Maya priests were the most highly educated of all Maya. They were considered the keepers of knowledge. They learned to read and write and taught those skills to the sons of nobles. They also studied astronomy and astrology and used the complex Maya calendar to advise on everything from when to plant crops to prophecies for kings, nobles and commoners. Priests kept track of family lines of succession, especially for Maya kings. With that combination of skills, you might say that priests were also Maya historians.

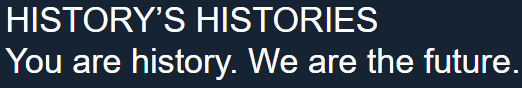

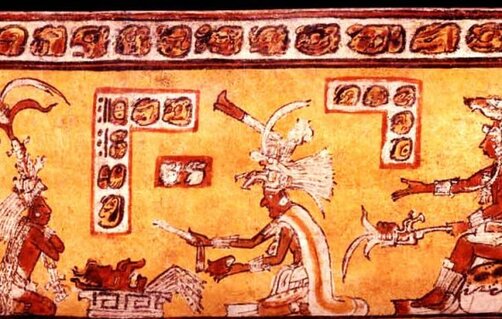

Maya priests performing a ritual in front of the seated king.

Maya priests performing a ritual in front of the seated king.

The Maya believed in lots and lots of gods and goddesses. Plants, animals, places, even rocks might have their own god or goddess. The Maya believed that every part of their lives held religious meaning and that their priests could talk to the gods. Therefore, one of the most important things that the priests did was to host religious ceremonies.

Because the Maya had so many gods, at least once a month everyone from the king to commoners attended religious ceremonies at which priests made offerings to the gods. The offering could be food or incense. It was often a bloodletting by the priests. Occasionally, the offering took the form of a human sacrifice. With so many ceremonies, taking charge of such events, talking with the gods, and interpreting the will of the gods was a major part of a priest’s life.

Because the Maya had so many gods, at least once a month everyone from the king to commoners attended religious ceremonies at which priests made offerings to the gods. The offering could be food or incense. It was often a bloodletting by the priests. Occasionally, the offering took the form of a human sacrifice. With so many ceremonies, taking charge of such events, talking with the gods, and interpreting the will of the gods was a major part of a priest’s life.

King Pa'Kal the Grat of Palenque.

King Pa'Kal the Grat of Palenque.

Leaders

At the very top of the social order were the Maya kings. The Maya civilization was not, however, an empire with one king ruling over a vast territory. Instead, a different noble family ruled each city-state. Larger cities might control smaller ones around them, receiving tribute or taxes in exchange for the protection of the king.

The king was considered a sacred ruler, one who governed by divine right. Believed to be the descendant of a god, a king’s authority was unquestioned and absolute. In Maya cities, the crown was handed down from father to son. In theory, the same family might rule forever, or at least until evidence arose that the king was no longer favored by the gods. Losing at war was a sure sign that a king had lost the favor of the gods.

At the very top of the social order were the Maya kings. The Maya civilization was not, however, an empire with one king ruling over a vast territory. Instead, a different noble family ruled each city-state. Larger cities might control smaller ones around them, receiving tribute or taxes in exchange for the protection of the king.

The king was considered a sacred ruler, one who governed by divine right. Believed to be the descendant of a god, a king’s authority was unquestioned and absolute. In Maya cities, the crown was handed down from father to son. In theory, the same family might rule forever, or at least until evidence arose that the king was no longer favored by the gods. Losing at war was a sure sign that a king had lost the favor of the gods.

The Maya had numerous powerful female rulers.

The Maya had numerous powerful female rulers.

While rule by a king was most common, a woman could rule and many did. If a woman did take power, however, it was usually as a widow of a king or as the mother of a prince. Still, many of the Maya women rulers were quite powerful, even participating in battle. The first female Maya ruler in Maya history was Lady Yohl Ik’nal of Palenque. Lady Yohl Ik’nal was also the mother of another female ruler, Lady Sak K’uk and the grandmother of Pa’kal the Great, one of the Maya’s most powerful kings.

Other notable female rulers include Lady Tikal. She reigned over the important religious and economic center of Tikal for 16 years. And, at least two female rulers were known not only as powerful rulers but also as warrior queens. Lady K’abal of Waká was given the name of kaloomte, or “supreme warlord,” by her city. And, Lady Six Sky is even described on stelae in Naranjo as a “warrior king.”

Questions:

1. Why are the Maya called the People of the Corn?

2. Name three classes in Maya society.

Other notable female rulers include Lady Tikal. She reigned over the important religious and economic center of Tikal for 16 years. And, at least two female rulers were known not only as powerful rulers but also as warrior queens. Lady K’abal of Waká was given the name of kaloomte, or “supreme warlord,” by her city. And, Lady Six Sky is even described on stelae in Naranjo as a “warrior king.”

Questions:

1. Why are the Maya called the People of the Corn?

2. Name three classes in Maya society.