India Indus Valley Civilization Activites

Unlocking the Secrets of Mohenjo Daro

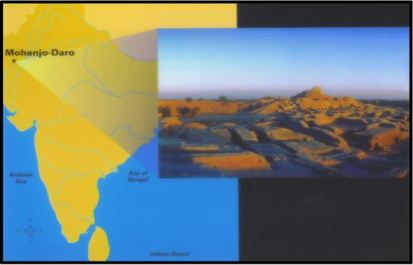

Introduction: Mohenjo-Daro, which scholars believe means "hill of the dead," was an ancient Indian city located on the west bank of the Indus River. The ruins of Mohenjo-Daro were discovered in 1922. The other Indus Valley city known at that time was Harappa, discovered in 1826. In the last century, thousands more ancient settlements have been discovered along the banks of the Indus River and the now-dried-up Saraswati River, and many of those settlements were at least as large as Mohenjo-Daro.

The people of Mohenjo-Daro belonged to what many scholars refer to as Harappan culture, named after the first excavated ancient city from the region. Because so many towns and cities have been discovered in the Indus Valley since Harappa was unearthed, each bearing similarities to the others, the ancient towns and cities of the Indus Valley are now referred to as the Indus Valley civilization. Sometimes you will also hear this ancient civilization called Harappan civilization. Keep in mind that each term is equally correct.

Indus Valley civilization represents the late stage of a cultural tradition that dates back to at least 6500 BCE. The Indus Valley civilization included a variety of ethnic groups and it flourished for 800 years, from approximately 2700 BCE until 1900 BCE. Many archaeologists and scholars focus on Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa when studying this culture because they were the earliest settlements discovered and have, therefore, been most thoroughly excavated. In fact, however, scientists have now uncovered cities throughout the region.

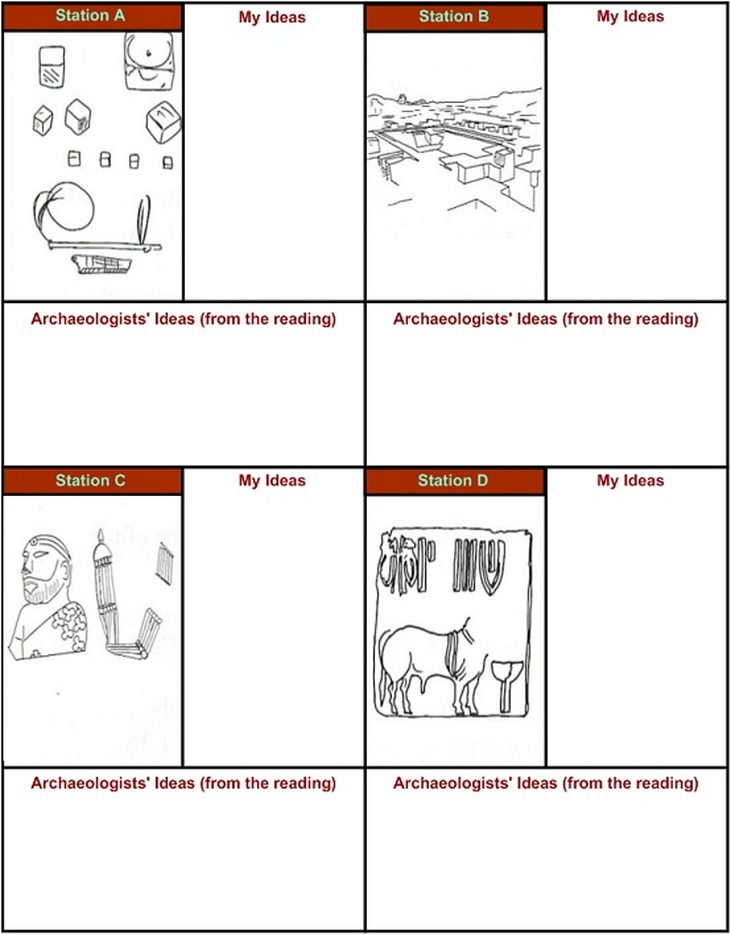

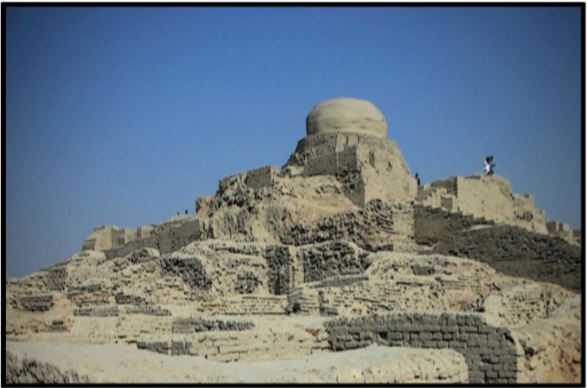

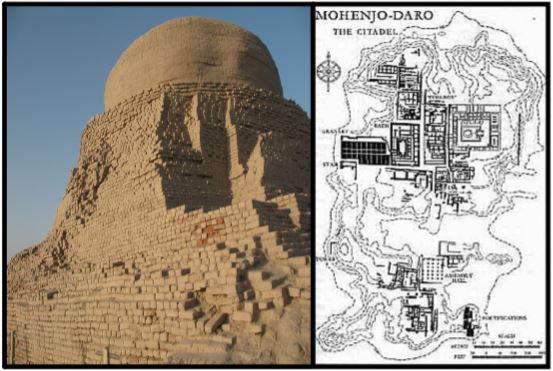

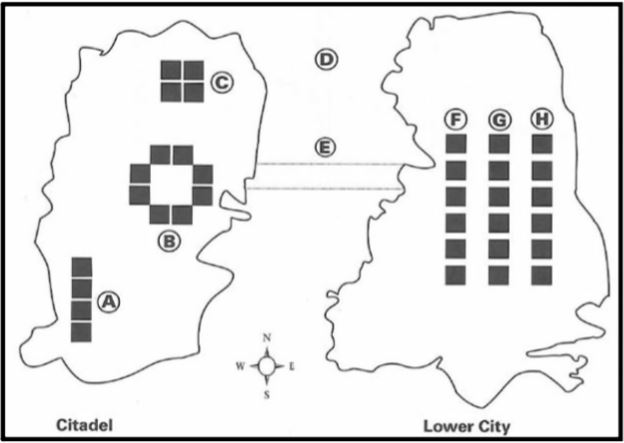

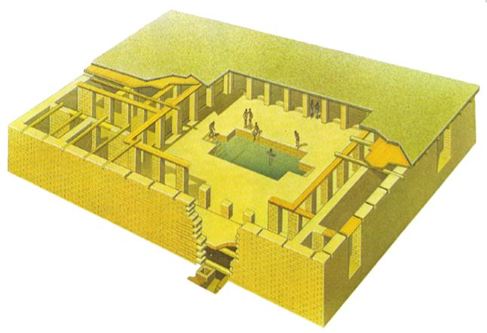

Mohenjo-Daro was an extremely well-planned city, similar in design to Harappa in the north. Both cities were approximately 3 miles in diameter and were laid out in the form of a grid with streets intersecting one another at right angles, a feature unseen in other ancient cultures. Homes and city walls were built primarily of burnt and unfired mud bricks. Like Harappa, Mohenjo-Daro was divided roughly into two areas - an elevated and fortified area, or citadel, to the west, and a lower city to the east. The citadel, pictured above, was home to buildings designed for public use, buildings such as the granary and the Great Bath. It was approximately 400 yards long and 200 yards wide, and it was built on a mud and brick platform that raised it 50 feet above the lower city. A wall surrounded the citadel and contained notches from which people could look out and defend the area from enemies. Because it was elevated, a citadel also protected the city's public structures from the flooding. The lower city primarily consisted of houses. Archaeologists have also discovered what they believe to be craft workshops in both parts of the city. Today, archaeologists continue to excavate various areas of Mohenjo-Daro, and their findings have helped to build our understanding of this great Indian civilization.

Interpret Instructions - Notes On Ancient Artifacts & Ruins of Mohenjo Daro: History is the stories that get told. Because we don't yet understand Harappan writing, the ruined cities and artifacts left behind tell the story of the people who lived and built a civilization in the region thousands of years ago.

For this exercise you will play the role of archaeologist. Use your reading and your Brainbox to complete the charts below. Please follow these instructions:

Indus Valley civilization represents the late stage of a cultural tradition that dates back to at least 6500 BCE. The Indus Valley civilization included a variety of ethnic groups and it flourished for 800 years, from approximately 2700 BCE until 1900 BCE. Many archaeologists and scholars focus on Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa when studying this culture because they were the earliest settlements discovered and have, therefore, been most thoroughly excavated. In fact, however, scientists have now uncovered cities throughout the region.

Mohenjo-Daro was an extremely well-planned city, similar in design to Harappa in the north. Both cities were approximately 3 miles in diameter and were laid out in the form of a grid with streets intersecting one another at right angles, a feature unseen in other ancient cultures. Homes and city walls were built primarily of burnt and unfired mud bricks. Like Harappa, Mohenjo-Daro was divided roughly into two areas - an elevated and fortified area, or citadel, to the west, and a lower city to the east. The citadel, pictured above, was home to buildings designed for public use, buildings such as the granary and the Great Bath. It was approximately 400 yards long and 200 yards wide, and it was built on a mud and brick platform that raised it 50 feet above the lower city. A wall surrounded the citadel and contained notches from which people could look out and defend the area from enemies. Because it was elevated, a citadel also protected the city's public structures from the flooding. The lower city primarily consisted of houses. Archaeologists have also discovered what they believe to be craft workshops in both parts of the city. Today, archaeologists continue to excavate various areas of Mohenjo-Daro, and their findings have helped to build our understanding of this great Indian civilization.

Interpret Instructions - Notes On Ancient Artifacts & Ruins of Mohenjo Daro: History is the stories that get told. Because we don't yet understand Harappan writing, the ruined cities and artifacts left behind tell the story of the people who lived and built a civilization in the region thousands of years ago.

For this exercise you will play the role of archaeologist. Use your reading and your Brainbox to complete the charts below. Please follow these instructions:

First, print out a copy of the chart.

Next, using just your chart in hand to complete this step, challenge yourself by looking at the archaeologist's sketch in the chart and recording in the appropriate boxes both what you think the object is AND what you think the artifact tells us about the people of the ancient Indus Valley. Complete all of the boxes titled "My Ideas" before moving on to the reading and filling in the remaining boxes on the chart.

Then, read the corresponding text and complete the "Notes on Artifacts and Ruins of Mohenjo-Daro" by recording what archaeologists think about the pictured artifacts. So that the information stays fresh in your mind, I suggest filling in your chart one section at a time, moving back and forth between your chart and your reading.

Look at the map above to locate where each of the artifacts was found at the Mohenjo-Daro site.

Next, using just your chart in hand to complete this step, challenge yourself by looking at the archaeologist's sketch in the chart and recording in the appropriate boxes both what you think the object is AND what you think the artifact tells us about the people of the ancient Indus Valley. Complete all of the boxes titled "My Ideas" before moving on to the reading and filling in the remaining boxes on the chart.

Then, read the corresponding text and complete the "Notes on Artifacts and Ruins of Mohenjo-Daro" by recording what archaeologists think about the pictured artifacts. So that the information stays fresh in your mind, I suggest filling in your chart one section at a time, moving back and forth between your chart and your reading.

Look at the map above to locate where each of the artifacts was found at the Mohenjo-Daro site.

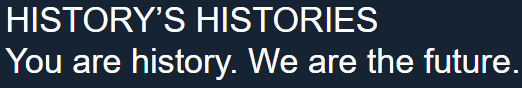

Area A: Stone Weights

The picture below shows weights of various sizes and a scale. These weights were discovered near a large building located on the citadel, just south and west of the Great Bath. This building is made of mud bricks and measures 150 feet long and 75 feet wide. It is referred to as the Granary. Archaeologists have also found bits of grain, such as wheat and barley, in the building's ruins. This has led some of them to speculate that the building was used to store grain and also to house workers who crushed the grain into flour for trade. Because farmers outside the walls of Mohenjo-Daro usually had their own granaries, some archaeologists think that grain stored within the citadel granary may have been collected as taxes. In addition, because of the presence of the weights, archaeologists have speculated that merchants weighted their grain and used it like money to buy and sell goods.

The picture below shows weights of various sizes and a scale. These weights were discovered near a large building located on the citadel, just south and west of the Great Bath. This building is made of mud bricks and measures 150 feet long and 75 feet wide. It is referred to as the Granary. Archaeologists have also found bits of grain, such as wheat and barley, in the building's ruins. This has led some of them to speculate that the building was used to store grain and also to house workers who crushed the grain into flour for trade. Because farmers outside the walls of Mohenjo-Daro usually had their own granaries, some archaeologists think that grain stored within the citadel granary may have been collected as taxes. In addition, because of the presence of the weights, archaeologists have speculated that merchants weighted their grain and used it like money to buy and sell goods.

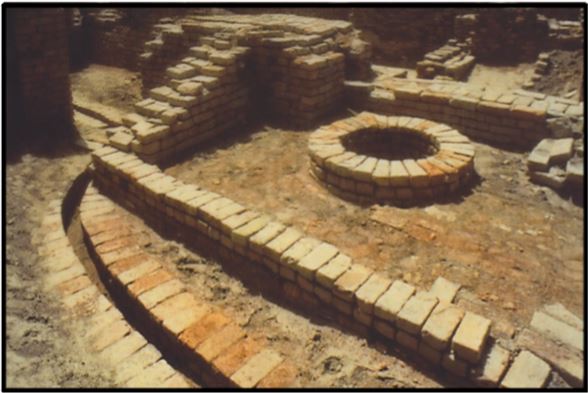

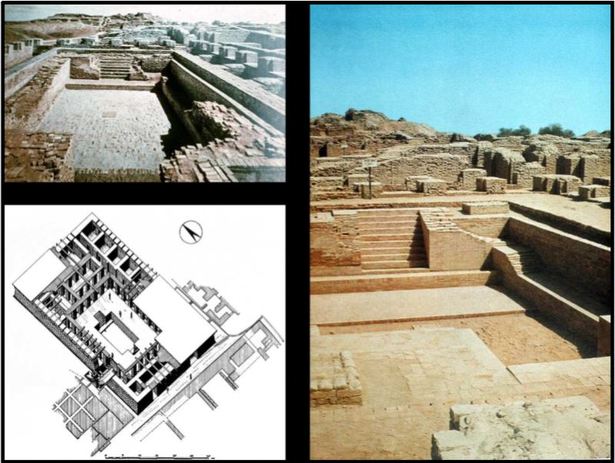

Area B: The Great Bath - Mohenjo-Daro

To the right are the ruins of the Great Bath in Mohenjo-Daro. Located on the citadel, this ruin contains a rectangular pool built from waterproofed brick. The pool measures 8 feet deep, 39 feet long, and 23 feet wide. The pool is surrounded by a series of small dressing rooms, one of which contains a well that supplied water to the bath. Used water was removed from the pool by way of a 6 foot high drain that ran along the west side of the Great Bath. The people of Mohenjo-Daro used the bath for hygienic purposes, and some archaeologists theorize that the Great Bath might have also been used in religious rituals. To support this theory, archaeologists point to the baths of later Hindu temples and the bathing rituals that remain an important part of modern Hinduism.

To the right are the ruins of the Great Bath in Mohenjo-Daro. Located on the citadel, this ruin contains a rectangular pool built from waterproofed brick. The pool measures 8 feet deep, 39 feet long, and 23 feet wide. The pool is surrounded by a series of small dressing rooms, one of which contains a well that supplied water to the bath. Used water was removed from the pool by way of a 6 foot high drain that ran along the west side of the Great Bath. The people of Mohenjo-Daro used the bath for hygienic purposes, and some archaeologists theorize that the Great Bath might have also been used in religious rituals. To support this theory, archaeologists point to the baths of later Hindu temples and the bathing rituals that remain an important part of modern Hinduism.

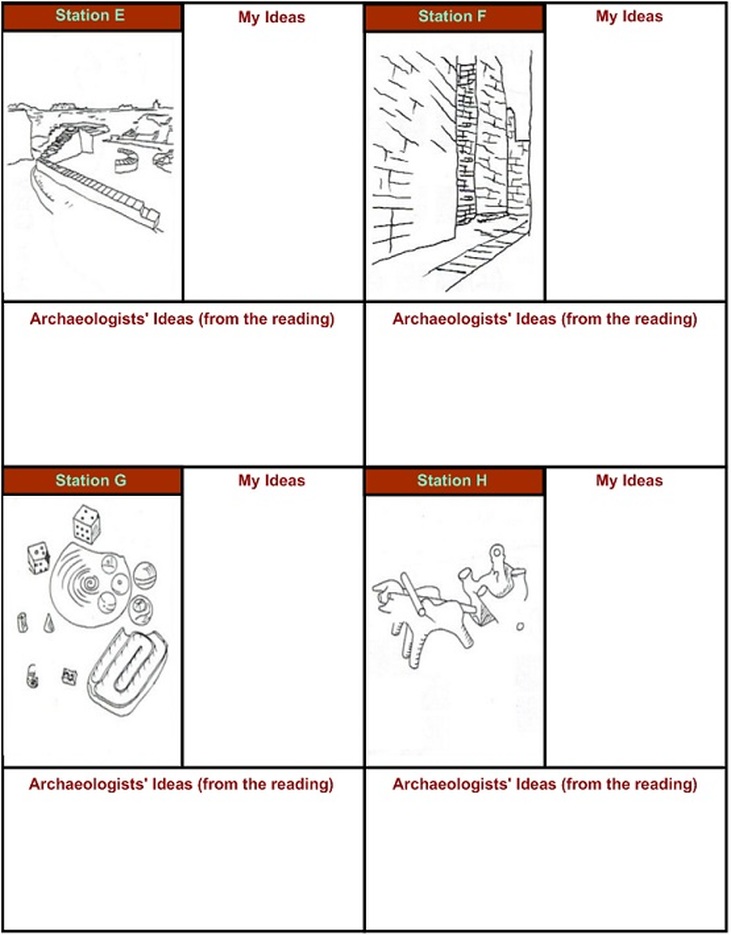

Area C: The Statues of Male & Female Figures and Necklace

Below are two statuettes and a bead necklace or belt found at Mohenjo-Daro. Little is known about the appearance of men and women in Mohenjo-Daro. However, this 7 inch stone sculpture discovered in the lower city shows how men in Mohenjo-Daro might have looked and dressed. The figure's beard is short and neat, his upper lip is shaved clean, and his hair is tied with a band that hangs down his back to his shoulders. A patterned robe covers his left shoulder, while his right shoulder is bare. Archaeologists once thought that this small statue was of a priest-king, but now they are uncertain whom it represents. Archaeologists believe that some of the female statues found in Mohenjo-Daro are fertility goddesses that might have been worshiped by the ancient Indians.

Many beautiful beads of blue lapis lazuli, red carnelian, and agate stones of all colors have been found throughout Mohenjo-Daro and were likely worn by the population's women. Holes drilled into the beads show that they were worn as necklaces, bracelets, earrings, finger rings, and other body decorations. Archaeologists have found beads in such locations as the Great Bath, where bathers probably lost them, and in the lower city, where bead makers may have dropped them in and around the kilns they used to make the beads.

Below are two statuettes and a bead necklace or belt found at Mohenjo-Daro. Little is known about the appearance of men and women in Mohenjo-Daro. However, this 7 inch stone sculpture discovered in the lower city shows how men in Mohenjo-Daro might have looked and dressed. The figure's beard is short and neat, his upper lip is shaved clean, and his hair is tied with a band that hangs down his back to his shoulders. A patterned robe covers his left shoulder, while his right shoulder is bare. Archaeologists once thought that this small statue was of a priest-king, but now they are uncertain whom it represents. Archaeologists believe that some of the female statues found in Mohenjo-Daro are fertility goddesses that might have been worshiped by the ancient Indians.

Many beautiful beads of blue lapis lazuli, red carnelian, and agate stones of all colors have been found throughout Mohenjo-Daro and were likely worn by the population's women. Holes drilled into the beads show that they were worn as necklaces, bracelets, earrings, finger rings, and other body decorations. Archaeologists have found beads in such locations as the Great Bath, where bathers probably lost them, and in the lower city, where bead makers may have dropped them in and around the kilns they used to make the beads.

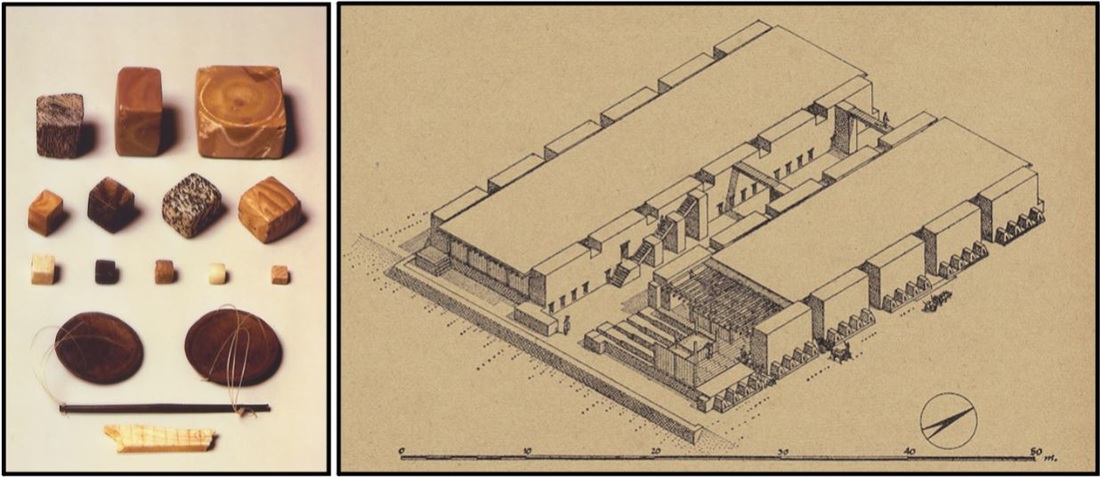

Area D: Four Seals

These are four seals engraved with various animals and writing. Found in large numbers all over the Mohenjo-Daro site, seals were generally carved from a soft stone called steatite. Small, the seals range from 3/4 of an inch to 1 3/4 inches in size. They are carved with pictographs (pictures or symbols used to represent an object, sound, or idea). Over 400 different pictographs have been identified, but very few have been deciphered. Most seals depict animals, such as buffalo, humped bull, tiger, elephant, rhinoceros, fish, and crocodile. There are seals that depict a cross-legged figure, which some scholars believe is an early version of the Hindu god, Shiva. Many of the seals have a boss, or small loop, on the back, which leads archaeologists to think that the people of Mohenjo-Daro may have worn them on a cord around their necks as amulets. Amulets are charms worn to protect the wearer from harm or evil. Archaeologists have also speculated that the seals were pressed into wax to make a sort of tag, perhaps showing which merchants owned what goods.

These are four seals engraved with various animals and writing. Found in large numbers all over the Mohenjo-Daro site, seals were generally carved from a soft stone called steatite. Small, the seals range from 3/4 of an inch to 1 3/4 inches in size. They are carved with pictographs (pictures or symbols used to represent an object, sound, or idea). Over 400 different pictographs have been identified, but very few have been deciphered. Most seals depict animals, such as buffalo, humped bull, tiger, elephant, rhinoceros, fish, and crocodile. There are seals that depict a cross-legged figure, which some scholars believe is an early version of the Hindu god, Shiva. Many of the seals have a boss, or small loop, on the back, which leads archaeologists to think that the people of Mohenjo-Daro may have worn them on a cord around their necks as amulets. Amulets are charms worn to protect the wearer from harm or evil. Archaeologists have also speculated that the seals were pressed into wax to make a sort of tag, perhaps showing which merchants owned what goods.

Area E: The Sewer System

Below left are the ruins of the sewer system showing some clay pipes and a well. Mohenjo-Daro's "chief glory" was a complex system of drains that ran throughout the city. According to one scholar, "only the Romans, more than two thousand years later, had a comparable drainage system." Clay pipes carried dirty, used water from buildings on the citadel and homes in the lower city to the main sewer system that ran along the city streets. The water and other sewage was emptied into the Indus River. This sewer system made it possible for both the rich and the poor to have bathrooms in their homes. Located throughout the city, there are also deep wells where people of Mohenjo-Daro stored their water.

Below left are the ruins of the sewer system showing some clay pipes and a well. Mohenjo-Daro's "chief glory" was a complex system of drains that ran throughout the city. According to one scholar, "only the Romans, more than two thousand years later, had a comparable drainage system." Clay pipes carried dirty, used water from buildings on the citadel and homes in the lower city to the main sewer system that ran along the city streets. The water and other sewage was emptied into the Indus River. This sewer system made it possible for both the rich and the poor to have bathrooms in their homes. Located throughout the city, there are also deep wells where people of Mohenjo-Daro stored their water.

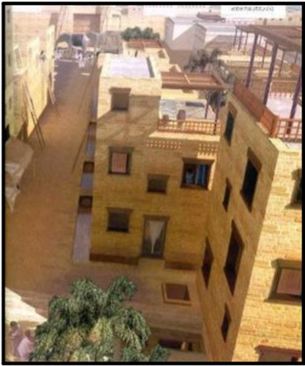

Area F: Homes

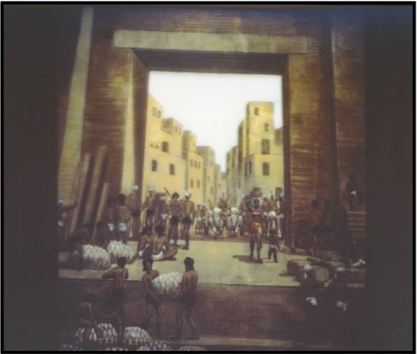

The computer generated image above right has brought Mohenjo-Daro back to life. Homes there were built close together along narrow alleys. Most of the people of Mohenjo-Daro lived in the lower city, an area to the east of the citadel and three times its size. Rows and rows of flat-roofed, two-story, mud-brick houses lined the streets. A home's windows were typically located on the second floor and were narrow and covered with screens made of a hard clay called terracotta or a translucent mineral called alabaster. The outside walls of homes in Mohenjo-Daro faced narrow alleys and their inside walls faced an open courtyard. Many of the houses had indoor bathrooms that drained into the main sewer system that ran throughout the city streets. Archaeologists have excavated houses containing one room and houses containing more than a dozen rooms. They have speculated that the one-room houses belonged to the poorer citizens of Mohenjo-Daro and the multi-room houses to the wealthier.

Area G: Games

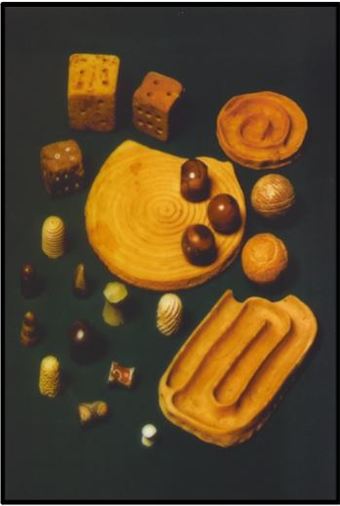

The picture to the right shows dice, carved pawns, balls carved of stone, and clay tracks. Archaeologists think that these artifacts uncovered at Mohenjo-Daro were used to play games. Their findings include dice, solid stone boards, and carved "pawns" that they speculate might have been used to play an ancient form of chess. As evidence for this, archaeologists point to an ancient Indian work written in the sixth century BCE, the Bhavishya Purana. The Purana describes a war game played with dice and pawns that game historians believe is the predecessor to modern chess. The Purana refers to this game as Chaturanga, or "four parts." Archaeologists have also found toys consisting of grooved tracks made of baked clay and balls carved out of stone.

The computer generated image above right has brought Mohenjo-Daro back to life. Homes there were built close together along narrow alleys. Most of the people of Mohenjo-Daro lived in the lower city, an area to the east of the citadel and three times its size. Rows and rows of flat-roofed, two-story, mud-brick houses lined the streets. A home's windows were typically located on the second floor and were narrow and covered with screens made of a hard clay called terracotta or a translucent mineral called alabaster. The outside walls of homes in Mohenjo-Daro faced narrow alleys and their inside walls faced an open courtyard. Many of the houses had indoor bathrooms that drained into the main sewer system that ran throughout the city streets. Archaeologists have excavated houses containing one room and houses containing more than a dozen rooms. They have speculated that the one-room houses belonged to the poorer citizens of Mohenjo-Daro and the multi-room houses to the wealthier.

Area G: Games

The picture to the right shows dice, carved pawns, balls carved of stone, and clay tracks. Archaeologists think that these artifacts uncovered at Mohenjo-Daro were used to play games. Their findings include dice, solid stone boards, and carved "pawns" that they speculate might have been used to play an ancient form of chess. As evidence for this, archaeologists point to an ancient Indian work written in the sixth century BCE, the Bhavishya Purana. The Purana describes a war game played with dice and pawns that game historians believe is the predecessor to modern chess. The Purana refers to this game as Chaturanga, or "four parts." Archaeologists have also found toys consisting of grooved tracks made of baked clay and balls carved out of stone.

Area H: Clay Figurines

This assembly of clay figures includes a tiger, an elephant, and a pottery-filled cart pulled by two bulls. These models are made of terracotta. Archaeologists believe the cart model shows how farm goods might have been transported from the fields outside of Mohenjo-Daro to the city market. These goods probably included wheat, barley, cotton, rice, melons, peas, sesame seeds, and dates. Many small clay figures of humans and animals have been found at the Mohenjo-Daro site, and scientists believe children may have played with toy-like terracotta models such as these.

This assembly of clay figures includes a tiger, an elephant, and a pottery-filled cart pulled by two bulls. These models are made of terracotta. Archaeologists believe the cart model shows how farm goods might have been transported from the fields outside of Mohenjo-Daro to the city market. These goods probably included wheat, barley, cotton, rice, melons, peas, sesame seeds, and dates. Many small clay figures of humans and animals have been found at the Mohenjo-Daro site, and scientists believe children may have played with toy-like terracotta models such as these.

Brain Work Questions

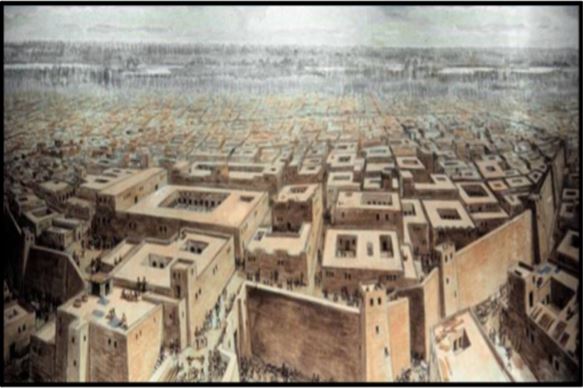

Think Instructions: First, print a copy of the questions. Then, look at the artist's rendition of what Mohenjo-Daro might have looked like when it was a thriving city below. Next, citing evidence from the text and pictures in your answer, respond to the following questions.

Please write complete sentences and do your best to use proper spelling, grammar, and punctuation.

1. What have you learned about daily life in Mohenjo-Daro from this activity?

2. Which aspects of daily life in Mohenjo-Daro do you see represented in the artist's picture below?

Please write complete sentences and do your best to use proper spelling, grammar, and punctuation.

1. What have you learned about daily life in Mohenjo-Daro from this activity?

2. Which aspects of daily life in Mohenjo-Daro do you see represented in the artist's picture below?

3. In what ways was Mohenjo-Daro like a modern city?

4. Why is it difficult for us to know exactly what life was like in ancient civilizations such as those in the Indus Valley region?

5. What do you think might have contributed to the decline of Mohenjo-Daro?

4. Why is it difficult for us to know exactly what life was like in ancient civilizations such as those in the Indus Valley region?

5. What do you think might have contributed to the decline of Mohenjo-Daro?

Covering Mohenjo-daro

|

Conclusion: After flourishing for nearly a thousand years, by around 1900 BCE the Indus Valley civilization began to decline. The most popular explanation for this decline used to be that groups of warriors from central Asia, called Aryans, entered India from the northwest through the mountain passes of modern Afghanistan and conquered the people of the Indus Valley. However, the lack of archaeological evidence to support this theory has encouraged many scholars to seriously question it.

Current research suggests that sometime around 1900 BCE, a series of major tectonic shifts resulted in multiple, major earthquakes. It's possible this seismic activity was accompanied by volcanic eruptions, as well. As a result, the flow of life - supporting rivers such as the Saraswati and the Indus may have been altered, causing great hardships for the people of the Indus Valley. While there is no clear evidence that the Indus Valley settlements were destroyed by earthquakes, there is evidence that a number of sites were destroyed or damaged by floods. Many other sites appear to have been abandoned by people because the rivers changed course. |

Some scholars believe that following these geological events, the people of the Indus region moved eastward into the fertile valley of the Ganga River and its tributaries. While the Indus Valley was not entirely abandoned after that sizable migration, the communities that remained were considerably smaller than those at the height of Indus Valley civilization.

|

|

|

Create Instructions: This is an EITHER/OR activity. You must complete ONLY one of the following tasks.

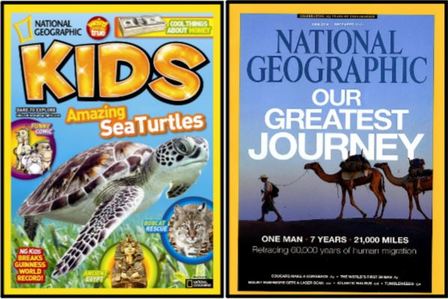

If you choose Task A, you will create a National Geographic Magazine cover. This is an individual task.

If you choose Task B, you will create a wordless picture book. For this activity, you may work with up to two of your classmates, forming a group of three.

If you choose Task C, you will write a fantasy story.

Please read and follow the directions for each task below. Remember, you only need to complete one task.

A) National Geographic Magazine Cover:

Use Google Drawing or another design program to create a cover for an issue of National Geographic Magazine using words and visuals that highlight archaeological discoveries made at Mohenjo-Daro. Your cover MUST include:

If you choose Task A, you will create a National Geographic Magazine cover. This is an individual task.

If you choose Task B, you will create a wordless picture book. For this activity, you may work with up to two of your classmates, forming a group of three.

If you choose Task C, you will write a fantasy story.

Please read and follow the directions for each task below. Remember, you only need to complete one task.

A) National Geographic Magazine Cover:

Use Google Drawing or another design program to create a cover for an issue of National Geographic Magazine using words and visuals that highlight archaeological discoveries made at Mohenjo-Daro. Your cover MUST include:

- Imaginative subtitles,

- A minimum of three visuals of artifacts from Mohenjo-Daro, and

- Brief captions that explain what each artifact reveals about daily life in Mohenjo-Daro.

B) Wordless Picture Book: Although the people in the Indus Valley wrote things down, even today, archaeologists cannot read their script. We can read cuneiform from Mesopotamia because a stone was found with the same thing written in three different languages. Archaeologists could read two of them, so they could figure out the third. No such stone has yet been found in the hundreds of towns and cities that have been discovered in the Indus Valley.

In fact, archaeologists really haven’t found that much written down. It may be that the ancient Harappans used paper, or something else that did not survive. It’s a real mystery.

Since we can’t read their script, today you will create a wordless book about daily life in the Indus Valley 5,000 years ago. Using the reading, draw pictures that capture what Harappan daily life must have been like. Please color your pictures.

In fact, archaeologists really haven’t found that much written down. It may be that the ancient Harappans used paper, or something else that did not survive. It’s a real mystery.

Since we can’t read their script, today you will create a wordless book about daily life in the Indus Valley 5,000 years ago. Using the reading, draw pictures that capture what Harappan daily life must have been like. Please color your pictures.

C) Fantasy Story: There are many mysteries about the ancient Indus Valley civilization.

We know that water was very important to the early people who lived in the Indus Valley. They of course needed water to drink, which was supplied by rainwater and the Indus River. They also built private wells, for a handy and safe water supply. Almost all homes had a place to bathe inside, with a tunnel to handle runoff wastewater. There were huge public bathing platforms built where archaeologists believe the women met to wash clothes and socialize. Huge drains were built to handle sewage and water runoff for the entire city.

In each sizable Indus town, a huge pool was carefully built in or near the center of town. Some archaeologists believe these pools were public water tanks, places to store water. Some are beginning to refer to the pool as the great bath. Some guess that the pool was used for religious ceremonies. But the truth is, no one knows why these pools were built in each town. What they do know is that the pool was quite large. It was about 40 feet long, 20 feet wide, and about 8 feet deep.

The great bath was built deep enough so that, if it was filled with water, and you were standing on the bottom of the pool, the water would be over your head. On each end, wide steps led down into the pool. A ledge ran along each side, a place to stand without having to tread water to stay alive. Your head and most of your body would be out of the water.

Your job is to create a story, a fantasy, about the great pool. Since no one knows why these pools were built, your first step is to assign a reason for the construction of such pools. Then, based on that reason, write a story that tells the class the reason for the pool without actually stating it. When you read your story aloud, it will be up to the class to guess what purpose your pool had for the ancient Harappan people.

We know that water was very important to the early people who lived in the Indus Valley. They of course needed water to drink, which was supplied by rainwater and the Indus River. They also built private wells, for a handy and safe water supply. Almost all homes had a place to bathe inside, with a tunnel to handle runoff wastewater. There were huge public bathing platforms built where archaeologists believe the women met to wash clothes and socialize. Huge drains were built to handle sewage and water runoff for the entire city.

In each sizable Indus town, a huge pool was carefully built in or near the center of town. Some archaeologists believe these pools were public water tanks, places to store water. Some are beginning to refer to the pool as the great bath. Some guess that the pool was used for religious ceremonies. But the truth is, no one knows why these pools were built in each town. What they do know is that the pool was quite large. It was about 40 feet long, 20 feet wide, and about 8 feet deep.

The great bath was built deep enough so that, if it was filled with water, and you were standing on the bottom of the pool, the water would be over your head. On each end, wide steps led down into the pool. A ledge ran along each side, a place to stand without having to tread water to stay alive. Your head and most of your body would be out of the water.

Your job is to create a story, a fantasy, about the great pool. Since no one knows why these pools were built, your first step is to assign a reason for the construction of such pools. Then, based on that reason, write a story that tells the class the reason for the pool without actually stating it. When you read your story aloud, it will be up to the class to guess what purpose your pool had for the ancient Harappan people.