China Han Dynasty Biography Activity

#3 Merchants

Merchants of the Han empire were made up of various occupations. It included traders, moneylenders, animal breeders, and people who worked in mining and manufacturing. Many merchants had more than one occupation. For example, one merchant might be an animal breeder, a trader and a salt manufacturer.

Although they were part of the commoner class, most merchants were quite wealthy. Some of the richest merchants were those who took the money they made and invested it in land. These people accumulated great fortunes and acquired vast estates. It was not unusual for a merchant to own a large estate that contained hunting parks and fishponds and that was served by more than 1,000 slaves.

Wealthy merchants enjoyed a luxurious, pleasant life, similar in many ways to that of nobles and high officials. Some wealthy merchants dressed in fine silk. They kept the fastest horses and rode in fine carriages. They ate nothing but the best foods - the same fine meats (beef, mutton, and pork) and cereals (wheat and barley) that nobles and high officials ate. For a time, merchants enjoyed nearly the same superior social status as those at higher levels of Han society.

During the later part of the Han dynasty, the status of the wealthy merchants changed. Their great fortunes and landholdings became a threat to some people, particularly those in the class held by government officials. The Han government passed regulations to restrict and punish merchants to prevent them from becoming more powerful.

Under these regulations, the emperor sent many merchants, their sons, and their grandsons to far-off places to join the military and become frontier guards. The government also heavily taxed the property of merchants. If merchants failed to report their income, or made a false report, the government took away, or confiscated, their property. Some rules were passed just to humiliate merchants. One rule prevented them from wearing fine silk clothing, carrying weapons, and riding horses. The government also prohibited merchants from owning land and becoming officials. These last two laws, however, were not always effective and were rarely enforced.

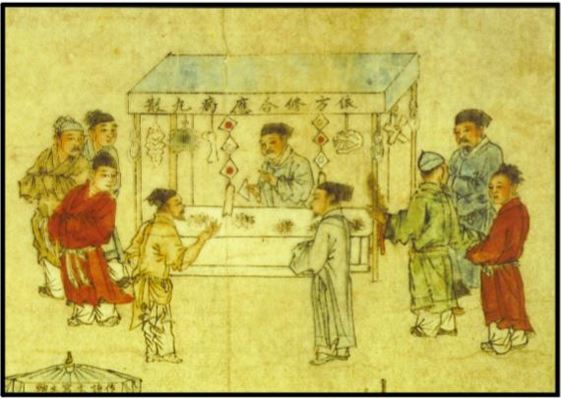

Not all merchants were wealthy. There were other merchants, such as peddlers and shopkeepers, who had much less money and property. They sold everyday necessities, items produced by farms and workshops, to commoners. These merchants often worked in the great public markets in large cities, such as the capital. They sold their goods in an atmosphere made lively by street acrobats, storytellers, and visiting foreigners. Shopkeepers sold objects of bronze, leather, silk, and wood, as well as food and drink. These merchants - unlike those with great fortunes and vast estates - lived on their small profits and lived modest lives.

Although they were part of the commoner class, most merchants were quite wealthy. Some of the richest merchants were those who took the money they made and invested it in land. These people accumulated great fortunes and acquired vast estates. It was not unusual for a merchant to own a large estate that contained hunting parks and fishponds and that was served by more than 1,000 slaves.

Wealthy merchants enjoyed a luxurious, pleasant life, similar in many ways to that of nobles and high officials. Some wealthy merchants dressed in fine silk. They kept the fastest horses and rode in fine carriages. They ate nothing but the best foods - the same fine meats (beef, mutton, and pork) and cereals (wheat and barley) that nobles and high officials ate. For a time, merchants enjoyed nearly the same superior social status as those at higher levels of Han society.

During the later part of the Han dynasty, the status of the wealthy merchants changed. Their great fortunes and landholdings became a threat to some people, particularly those in the class held by government officials. The Han government passed regulations to restrict and punish merchants to prevent them from becoming more powerful.

Under these regulations, the emperor sent many merchants, their sons, and their grandsons to far-off places to join the military and become frontier guards. The government also heavily taxed the property of merchants. If merchants failed to report their income, or made a false report, the government took away, or confiscated, their property. Some rules were passed just to humiliate merchants. One rule prevented them from wearing fine silk clothing, carrying weapons, and riding horses. The government also prohibited merchants from owning land and becoming officials. These last two laws, however, were not always effective and were rarely enforced.

Not all merchants were wealthy. There were other merchants, such as peddlers and shopkeepers, who had much less money and property. They sold everyday necessities, items produced by farms and workshops, to commoners. These merchants often worked in the great public markets in large cities, such as the capital. They sold their goods in an atmosphere made lively by street acrobats, storytellers, and visiting foreigners. Shopkeepers sold objects of bronze, leather, silk, and wood, as well as food and drink. These merchants - unlike those with great fortunes and vast estates - lived on their small profits and lived modest lives.